The Key to Growth: Business Investment

Words: 1,501 Time: 7 Minutes

- The pivot with monetary policy post 2008

- Can we "undo" the COVID spending disaster?

- A shift back to business based investment will drive growth

Someone asked me a good question this week:

With 10-year yields trading around 4.50% (with the possibility to go higher) – why haven"t equities sharply corrected?

It"s a good question…

For example, on the surface, one might think equities would struggle given the zero risk premium investors are receiving.

But that has not been the case…

The stock market has withstood the sharp rise in bond yields (for now anyway).

However, I believe there is a simple explanation…

It"s the amount of liquidity in the system.

Liquidity is abundant – evidenced by the very low credit spreads (i.e., participants see very little risk)

Generally credit spreads widening are your first sign of trouble.

But let"s set the scene as to how we got here.

For example, there"s a lot of noise today about reducing the US debt burden and level of deficit spending (expected to be around $2T this year if this don"t course correct)

And from there, if we can get the debt levels down, then perhaps the bond vigilantes will back down from insisting on higher yields?

However, it raises a few questions. For example (and certainly not limited to):

- Is the level of debt and deficits warranted?

- Is it sustainable?

- Why is reducing debt important?

- If it"s reduced – could it impact near-term growth

- Can it be fixed? and

- If so… how (e.g. where should cuts be made and why)?

The last question of "how" is very hard.

For example, I don"t think it matters where any possible reduction is made – it will be faced with tremendous resistance.

But there"s a lot to explore – where our "monetary story" (and record debts) starts in 2008.

That"s when things started to unravel…

The Big Shift in Monetary Policy

To understand the explosion in public debts, deficits, money supply (and liquidity) we need to explain what we saw before 2009.

During that time, bank reserves were non-interest-bearing assets, meaning banks held the bare minimum required for regulatory purposes.

Therefore, to control inflation, the Federal Reserve (Fed) would restrict the supply of reserves, pushing up borrowing costs and slowing money supply growth.

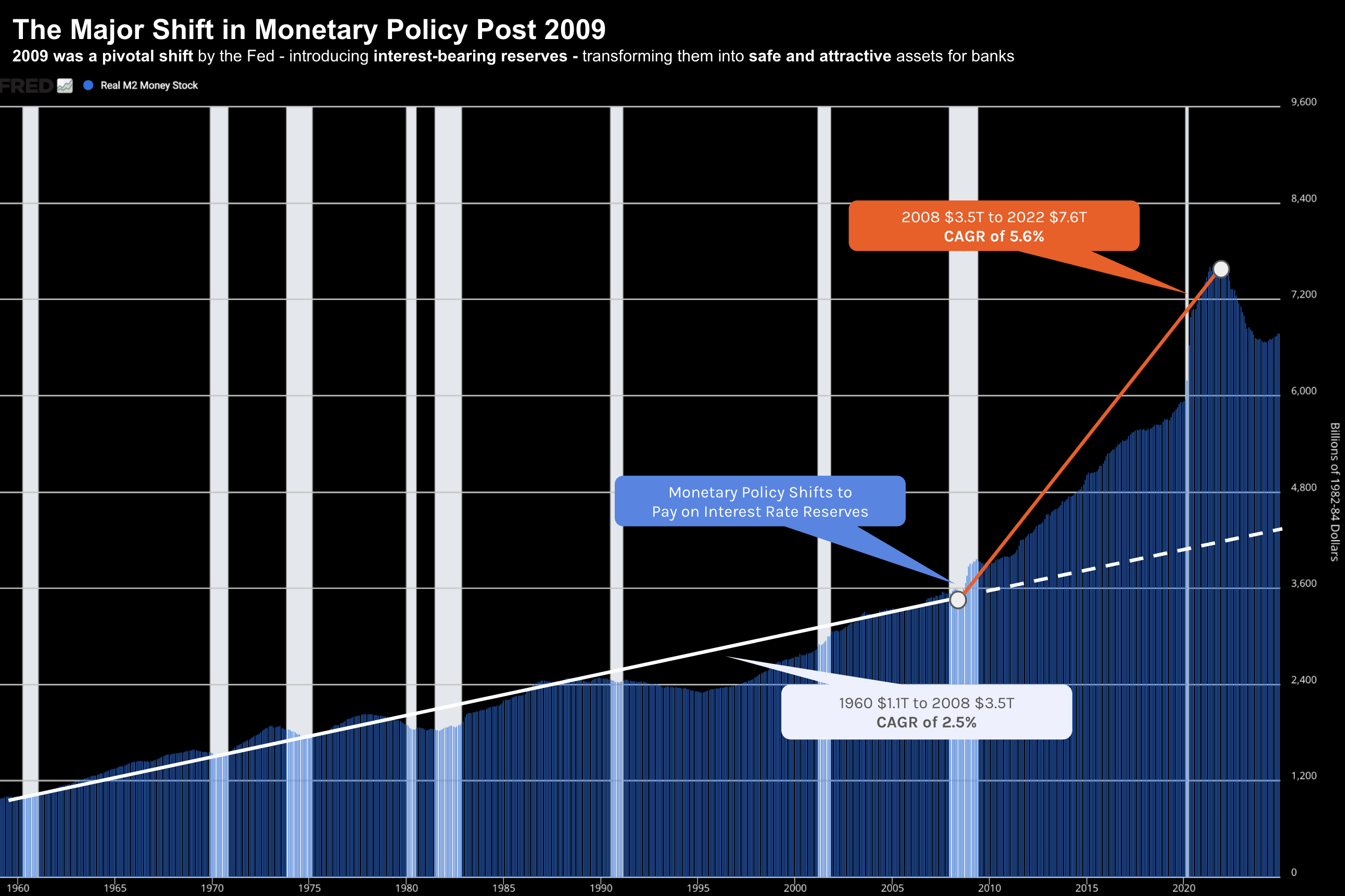

For example, from 1960 to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 – the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in Real M2 money stock was ~2.6% (solid white line below) – and slightly above inflation.

However, post the GFC, the CAGR in Real M2 exploded to 5.6% at the peak of 2022 (orange line).

The last time we saw something like this was WWII.

Now the traditional method of monetary policy arguably led to more recessions – often marked by rising credit spreads.

However, they were far less exaggerated.

As the chart shows above, towards the end of 2008, the Fed made a pivotal shift by introducing interest-bearing reserves, transforming them into safe and attractive assets for banks.

Instead of controlling reserves, the Fed directly influenced short-term interest rates.

Analysts initially feared this approach would trigger excessive lending and inflation.

However, inflation remained stable for around a decade as demand for (interest bearing) reserves matched their growing supply, preventing a surge in actual money circulation (i.e., it didn"t hit the system).

But then things changed again…

COVID resulted in creating one of the largest man-made financial mistakes in history…. where we are just beginning to understand its longer-term consequences.

COVID: Unleashing the Inflation Genie

When I first saw the Fed"s response to COVID (and other central banks) – I wrote "this could end up being the greatest man-made financial mistakes" in history.

It"s still too soon to see if that will be the case – as we are working through the full consequences of the damage done to central banks and government balance sheets.

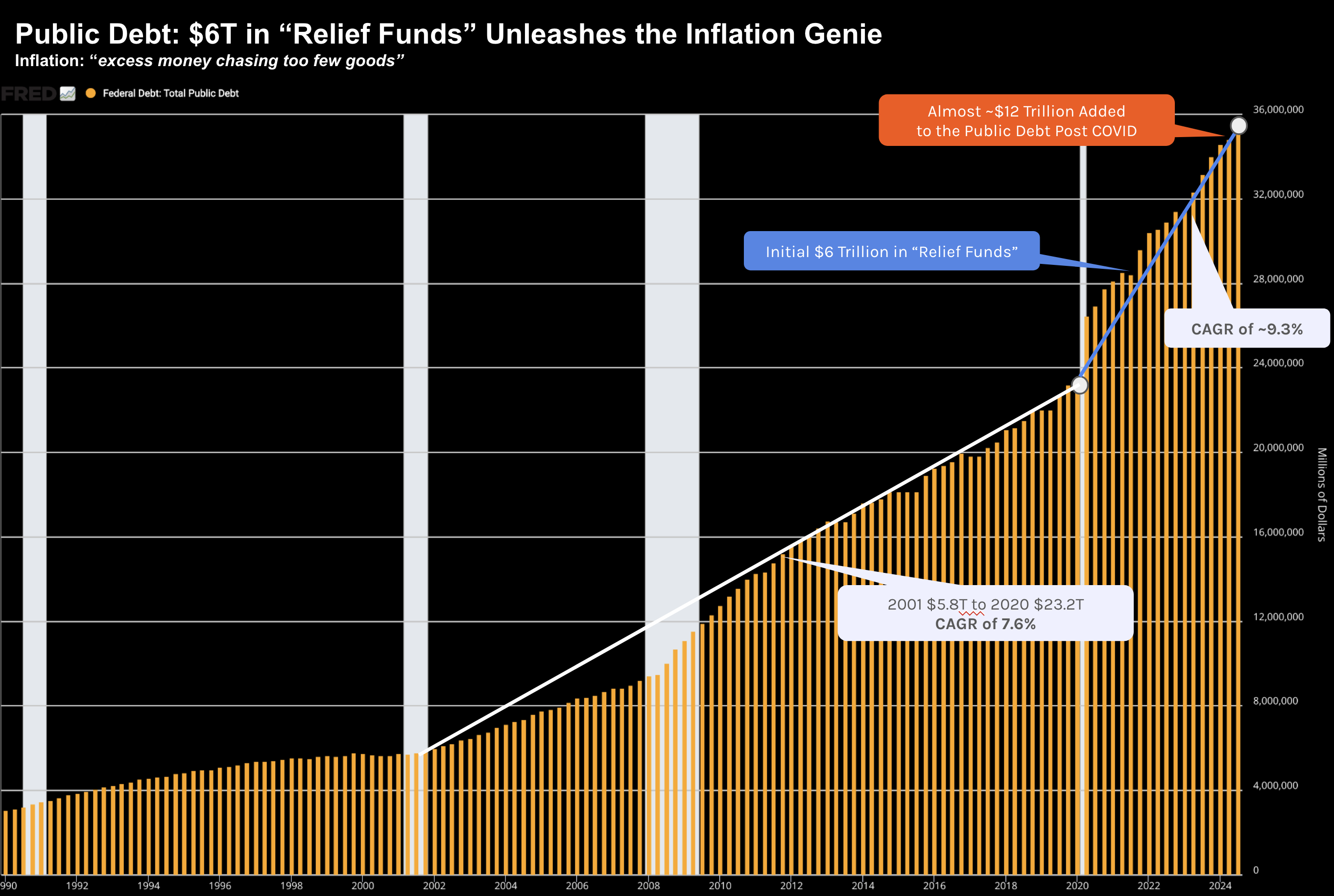

For example, below shows the surge in federal government"s public debt from 1990:

From 2001 to 2020 – this was growing at a "modest" rate of ~ 7.6% per year – however much faster than growth rates pre 2000.

However, the pandemic-induced economic shutdowns in 2020 led the U.S. Treasury to distribute $6 trillion in relief funds.

This was a mistake.

Public debt went from a level of around $23T (close to GDP) to $29T almost overnight.

However, compounding their error, since then public federal debt has exploded to ~$36T (now well in excess of GDP)

And this is your source of unwanted inflation…

Initially, much of this money remained idle in people"s savings accounts (estimated to be between $2T to $3T at the time).

However, as the economy reopened in 2021, pent-up demand clashed with supply chain disruptions, causing inflation to spike.

In short, we had"excess money chasing too few goods"

That"s the very definition of inflation.

For example, it mirrored Milton Friedman"s "helicopter money" analogy, where excessive liquidity led to sharp price increases.

By early 2021, it became evident that inflation would not be transitory (as the Fed told us).

The Fed was very slow to respond in March 2022 – starting to raise interest rates to curb spending and inflation.

At the time, many experts feared this tightening would cause a recession — as history typically shows.

However, given the unprecedented liquidity in the system (e.g. the $6+ Trillion in "relief money" and other government spending) – consumers were able to continue spending keeping the economy afloat.

What recession?

This very short (condensed) background was written to give you important context as to what I think could be ahead.

More specifically – what we need to see to get in front of the (financial) mess we "had" to create.

Long-Term Consequences…

The good news is inflation appears to be under control.

That said, prices are still rising, they are just not rising as fast. However, don"t expect them to go back.

But the long-term consequences of pandemic-era stimulus are still present (and will be for some time)

As I showed above, federal spending has surged the past four years – despite no signs of any economic emergency (e.g., like what we faced in 2020/21 or 2008/09).

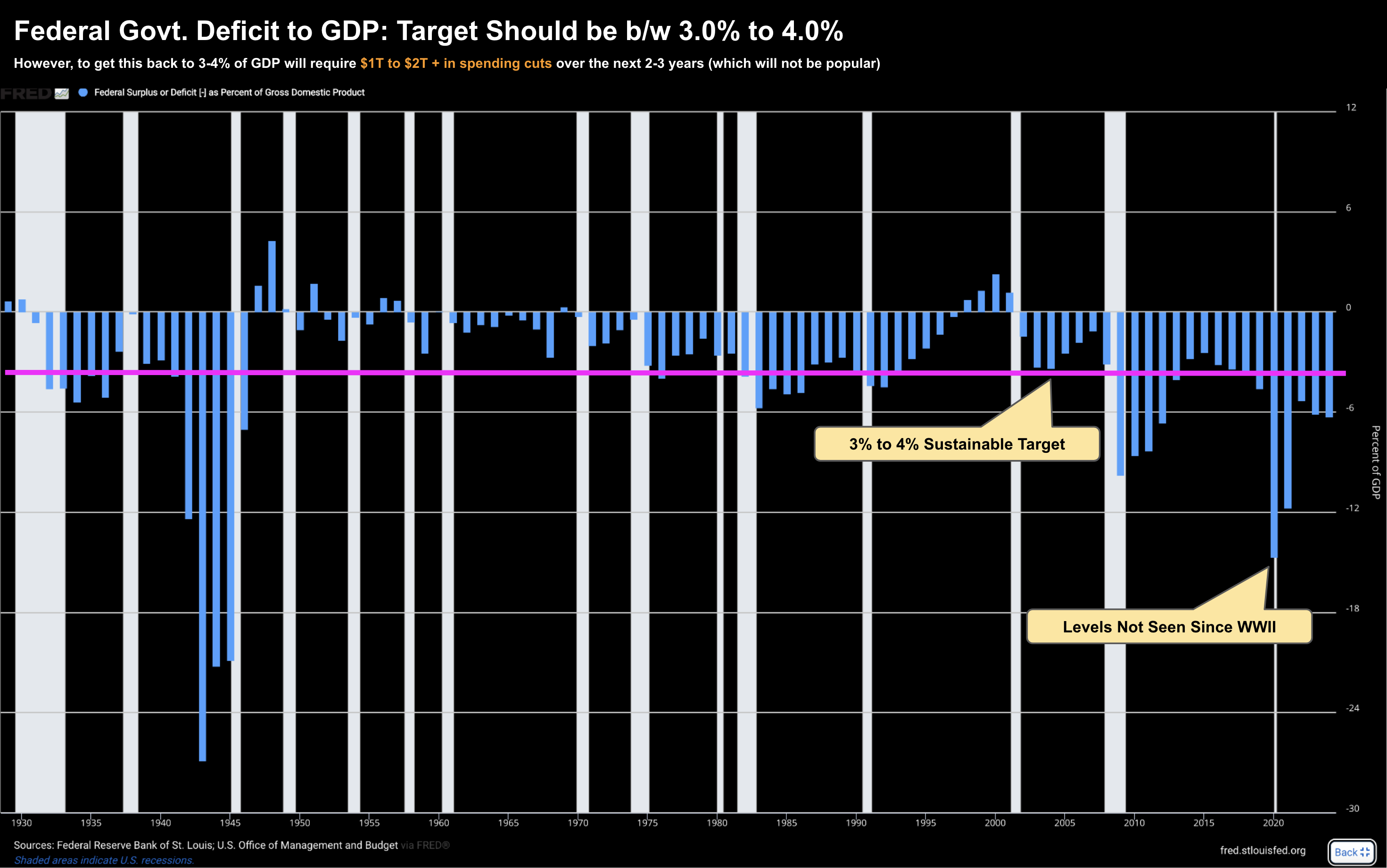

I shared this chart recently – showing the relative deficit-to-GDP ratios in recent years.

We have not seen anything like it since WWII.

As to whether we can get this back to a manageable 3-4% of GDP (the purple line) remains to be seen.

I"m not confident…

That said, what this shows (in addition to the public debt) is the clear shift of economic growth away from private sector investment toward government-driven expansion.

It"s the opposite of what we need to achieve (unless you are a state controlled economy like China).

For example, the federal deficit was once around $1 Trillion annually.

Today that number is closer to ~$2 Trillion (where annual deficits compound the total amount of debt).

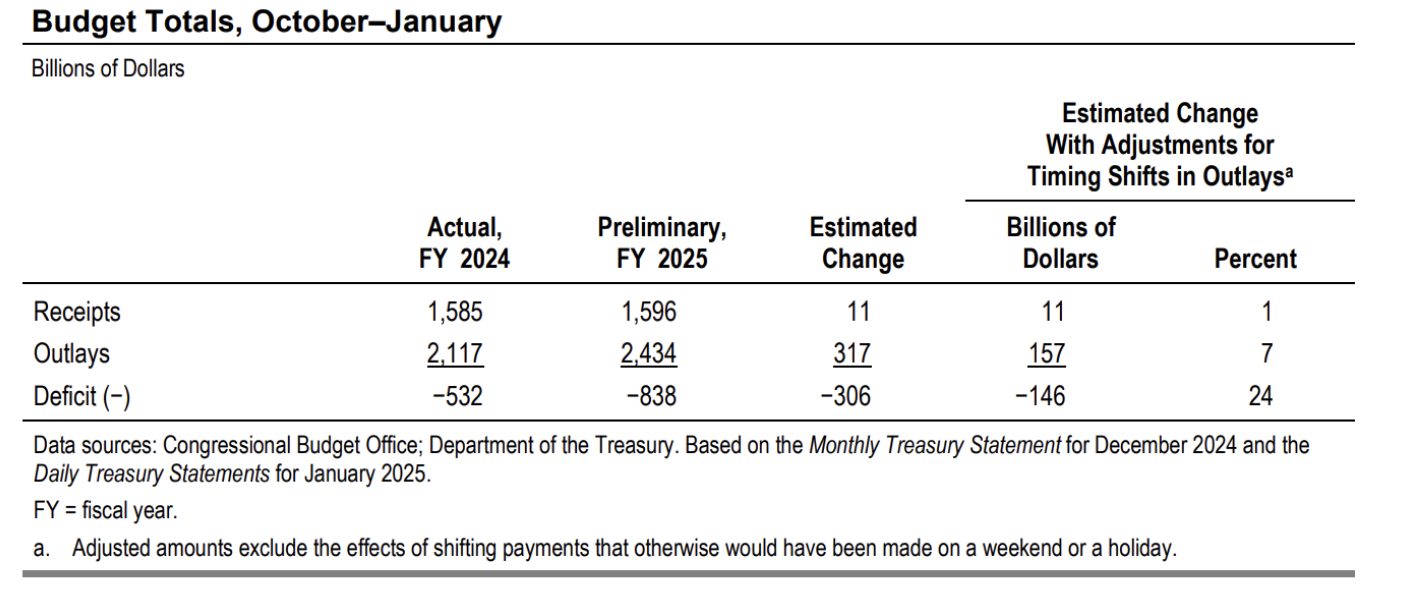

And for the first four months of fiscal year 2025 – the federal deficit was $838 billion, up $306 billion on the previous years (again, it"s on track to hit $2T this year)

This train has not slowed down… not yet.

Of particular note – outlays for net interest on the public debt increased by $37 billion (or 13%) primarily because the debt was larger than it was in the first four months of fiscal year 2024.

Now will something like DOGE fix this?

As I say… I have my doubts.

I think it"s far bigger than what they will be able to accomplish (that is if they can achieve any material reductions – as recommendations from DOGE need to go through Congress)

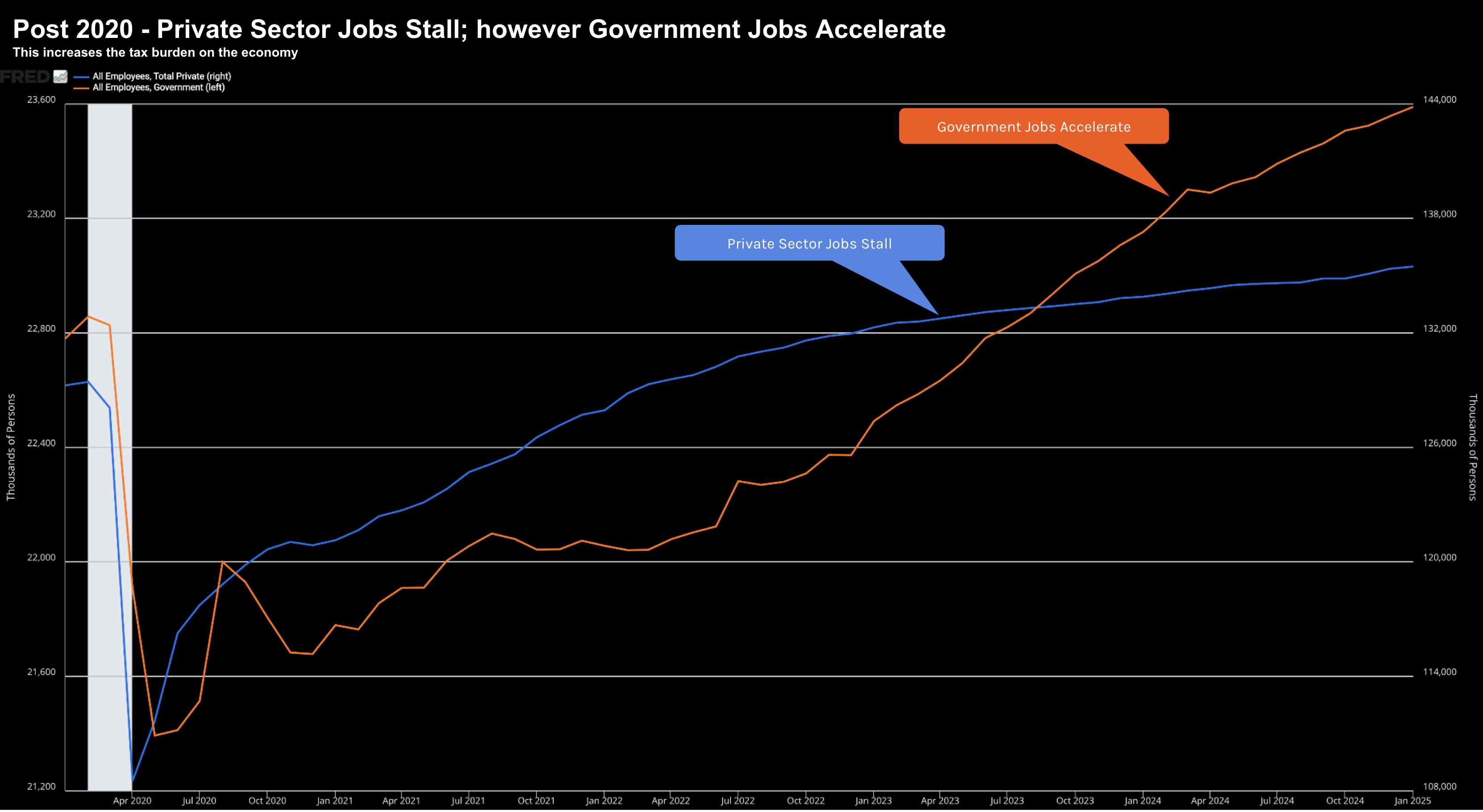

Beyond this, government jobs have grown at an annualized rate of over 2%, while private-sector job growth has slowed significantly.

From mine, this trend needs to reverse course.

The blue line (private sector jobs) should always outpace the orange line (government jobs).

Put it this way:

The goal should be more tax producing (private sector) jobs… with a steady level of government jobs (not one which accelerates – costing the tax payer money)

So What"s Ahead?

If only I knew…

As I wrote last week – I am worried about a growth scare coming down the pike.

As part of that post, I talked about three potential "anti-growth" policies from the Trump Administration.

Beyond the government attempting to get its fiscal house in order (where I have my doubts on whether DOGE will be successful) — the answer will not come from any central planning authority.

Yes, they can assist with policy…

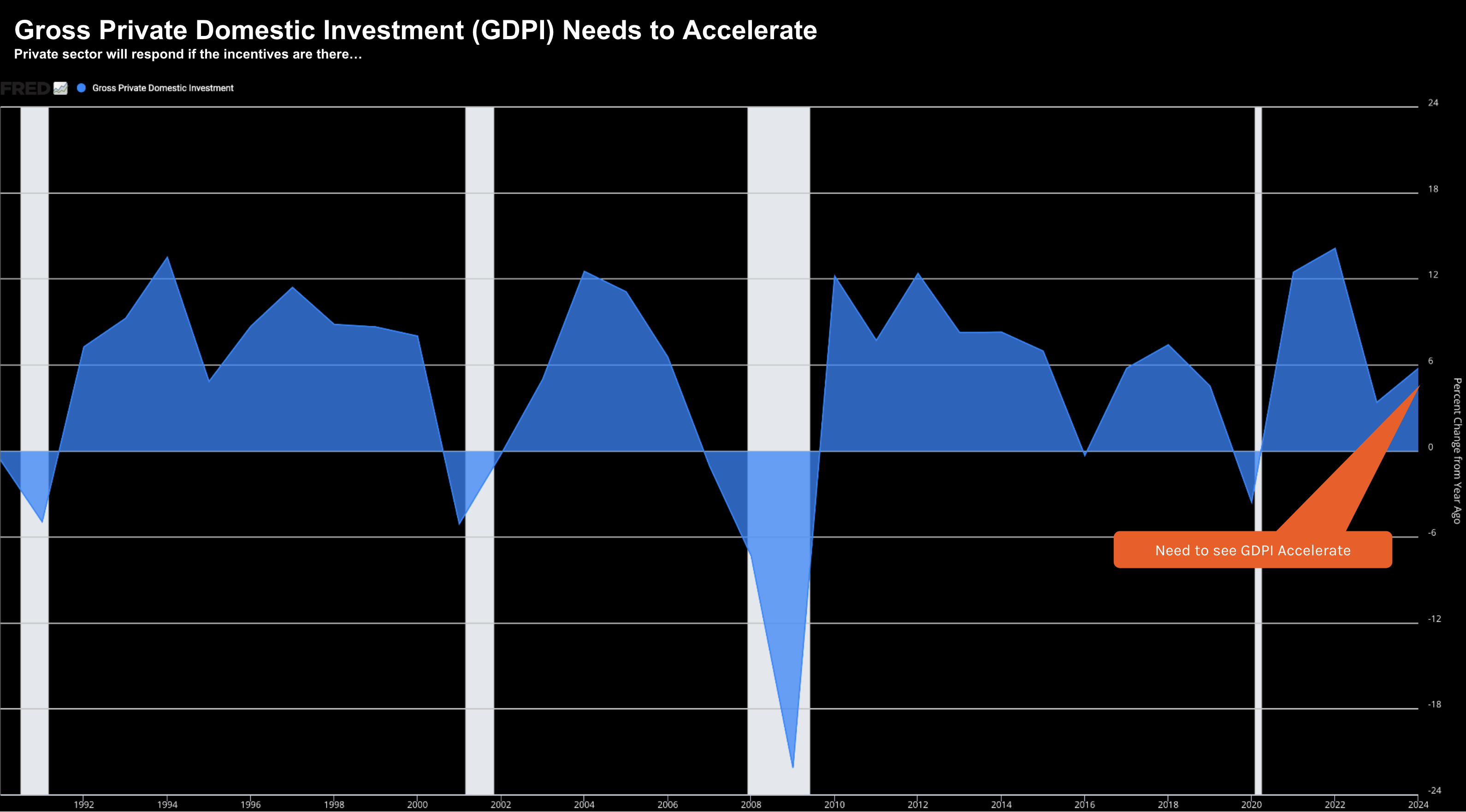

But economic growth will slow unless we see greater levels of private business investment.

Now historically, tight monetary policy has preceded recessions, however today we have an abundance of reserves.

This continues to cushion the market against any tightening we see with bond yields. However, if we continue to see:

- Excessive public sector debt and deficits (as a function of GDP); and

- Below average levels of gross domestic private-sector investment (see chart below)

… it follows that growth may struggle in the years ahead.

Putting it All Together

The unprecedented monetary experiment of the past twenty years will be studied for decades to come.

I"m divided as to whether it will be recorded as a success.

Ask me in another 20 to 30 years…

I say that because there are consequences with excessive debt… no exceptions. However, we"re yet to feel them.

Rarely is there such thing as a free lunch. Someone always pays.

Going forward I see two essential pathways to get growth back on track:

- Manageable levels of debt and deficit spending (i.e., where the interest cost on the debt doesn"t exceed Medicare and Defense spending); and

- A sharp increase in the amount of private sector investment

Investment from the private sector is particularly important if we"re to "grow" our way out of debt.