AI Anxiety

- AI is impressive, but without daily reliance, pricing power and long-term returns remain uncertain

- Are AI valuations assuming unit economics will eventuate?

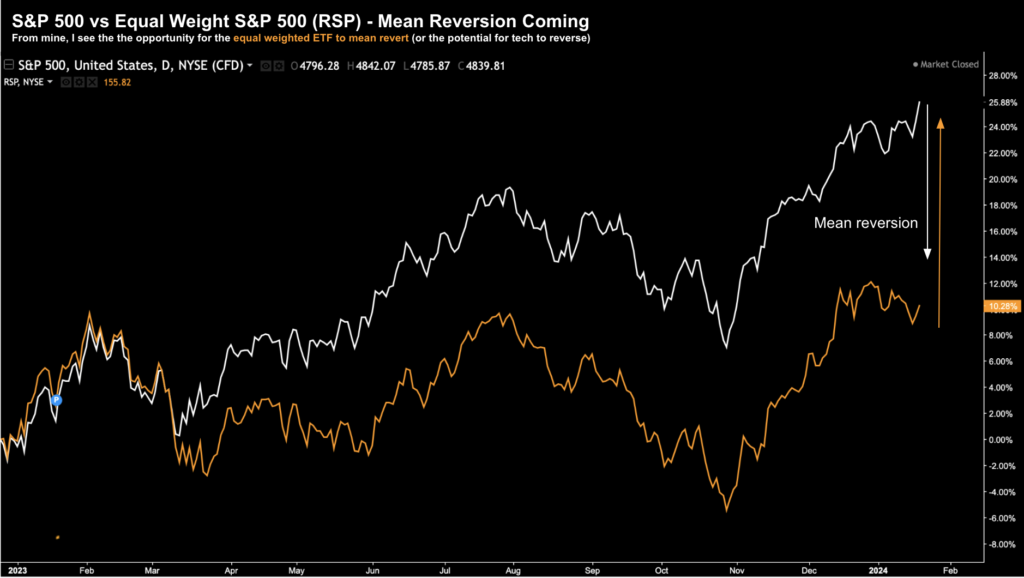

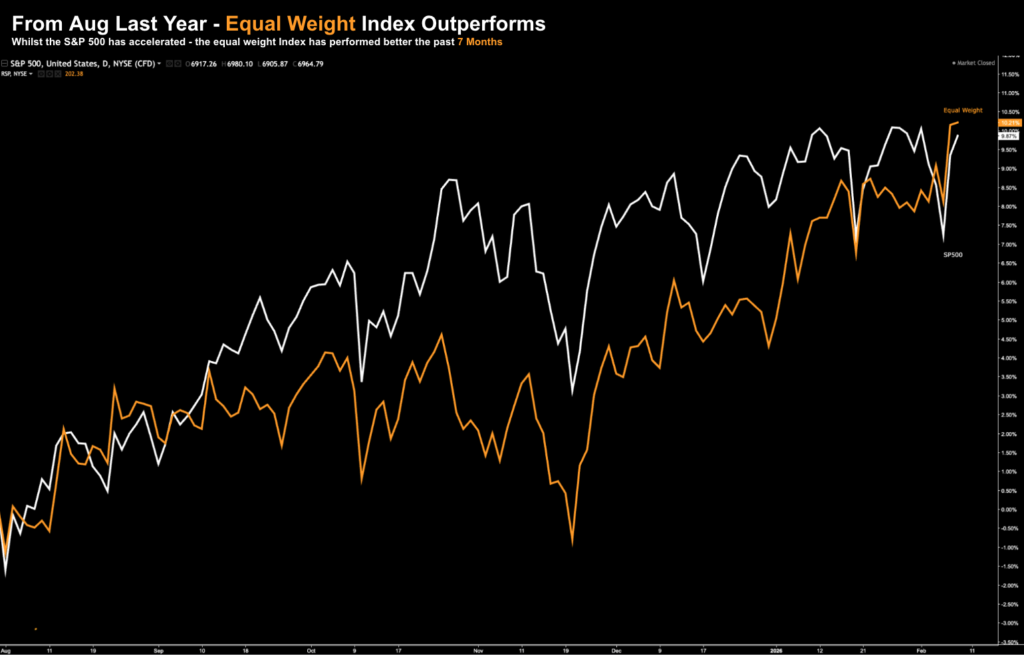

- Equal weight index outperforms the S&P 500 over past 7 months

What are the killer use case(s) for AI?

I"m asking because I don"t know.

Yes, any number of AI tools can summarise documents, generate code, draft emails, and surface insights buried in reports.

And for certain workflows, that"s undeniably useful.

That"s not the debate.

However usefulness is not the same as indispensability.

For example, for people whose work is conceptual, judgment-based, or relationship-driven, AI can feel more like an assistant than a necessity.

Sure it"s helpful at times and occasionally impressive — but at this stage – rarely mission critical.

When we zoom out to the broader population (which is what matters) – daily reliance for AI remains very thin.

Take Microsoft…

Microsoft told us last week that only about 3% of their 365 customers pay for Copilot. GitHub Copilot"s paid users are roughly 3% of registered developers.

This might help explain why their share price has lost 20% the past few months (more on this below when I talk to expected returns on capital given the multiples being paid)

Beyond Microsoft – several surveys suggest maybe 10% of people use generative AI every day. That"s not trivial but it"s not ubiquitous either.

Nate"s substack newsletter explored this point – citing Ben Evans.

Five themes emerged from Evan"s 90-slide talk:

- (1) From miracle to infrastructure: AI is becoming like electricity—not a tool you choose to use, but an ambient capability that changes what "differentiation" even means;

- (2) Path dependence is real: Where you deploy AI first shapes what becomes possible later. The wrong beachhead traps you in local problem sets while competitors run circles around you;

- (3) Buyer leverage is growing—if you design for it: Model convergence means you can arbitrage vendors, but only if you"ve built the architecture to do it;

- (4) AI is eating the org chart: This isn"t just a tech rollout. It"s an organizational restructuring that most leaders haven"t started planning for;

- (5) Daily AI use is good, but not enough: Evans calls out the adoption issue, and I go farther: I think the adoption gap is THE metric to obsess over to drive the rest

Big +1 to the last point.

For example, have you noticed that companies investing in the AI space prefer quoting weekly or monthly users.

Why?

Because daily engagement is the litmus test of product-market fit for mass market adoption.

Daily Active User (DAUs) is the harder number.

Think of it this way…

When you"re building a product for mass market use – you should ask whether your use-case is a:

- toothbrush test;

- laundry test; or

- rent test.

Tools like Search, Text, Email and Social are all good "toothbrush" tests. Most people use them at least once per day.

But if you"re solving for mass market – and you"re finding the pain point you"re solving for is either weekly or monthly – there is a lack of product market fit.

Sam Altman—OpenAI CEO – who understands the "toothbrush" necessity from his days at Reddit—emphasizes weekly active users (800M) rather than daily paid subscribers.

But he knows from his Reddit days that if you aren"t talking about DAUs – it"s because the "habit" hasn"t fully formed.

That"s not to say it won"t come (it could) – but for OpenAI investors – they have nearly $1 Trillion reasons to hope it does.

For now – investors are right to question the adoption gap.

Everything flows from there.

AI Anxiety

For much of the past decade, equity investing has been dominated by a simple, highly profitable formula.

Own the largest technology companies, avoid almost everything else, and let multiple expansion do the heavy lifting.

And it worked!

With incredibly high free cash flows; distinguishable competitive moats; returns on invested capital exceeding 25% – multiples in the range of 30x to 35x earnings were justified to own these names.

Scale, network effects, recurring revenue, and capital-light models justified high valuations.

The trade became self-reinforcing. Money flowed to what had worked, and what had worked kept working.

What we are seeing now is not necessarily the end of that era (it"s likely to run further) — but it may be the first serious challenge to its intellectual foundations.

Now if investors become less certain about future returns, they become less willing to pay extreme 35x plus multiples.

And this is becoming evident by what we see with the leadership in the market.

Over the past few months it"s stalled.

Market generals such as Meta, Microsoft and Amazon are well off their (AI) highs. Even the leading picks and shovels AI play – Nvidia – has treaded water for over 6 months.

What"s more, equal-weight benchmarks are now outperforming cap-weighted ones.

For example, sometime ago I made the case for the equal weight bench mark to mean revert against the broader S&P 500 (dominated by the Mag 7)

Let"s take a look at the past seven months:

Boring (non AI) sectors such as energy, staples, industrials, and international equities are outperforming.

Investors who for years were penalised for diversification are finding it rewarded.

This matters psychologically.

Concentration persists as long as alternatives fail. Once alternatives function, capital explores them.

The gravitational pull of the mega caps weakens not because they collapse, but because opportunity costs reappear.

Small caps are doing better than mega caps. Value is beating momentum. International markets are catching inflows.

That is not liquidation.

That is reassessment. And reassessment tends to be more important.

Here"s my take:

Growth expectations are now being reassessed. For years investors believed they knew exactly where durable growth would reside.

Now the formula that worked so well is less certain.

Why if a "nearly a trillion in capex" this year does not realize the same 20%+ ROIC the next few years?

What if the same (high) profit margins are no longer there?

The question is no longer whether these hyper-scalers will grow (they will) – it is whether these companies will capture value from growth.

Asset Light to Asset Heavy

One of the beautiful things about investing in the Mag 7 has been the relatively asset light nature of their business.

Again, due to their network effects, recurring revenue, and capital-light models — their margins and cash flows were unparalleled.

The software industry commanded extraordinary valuations because it appeared capable of scaling without proportionate reinvestment.

High incremental margins meant growth translated efficiently into free cash flow.

That was then…

Now the likes of Amazon guiding towards $200B in capex.

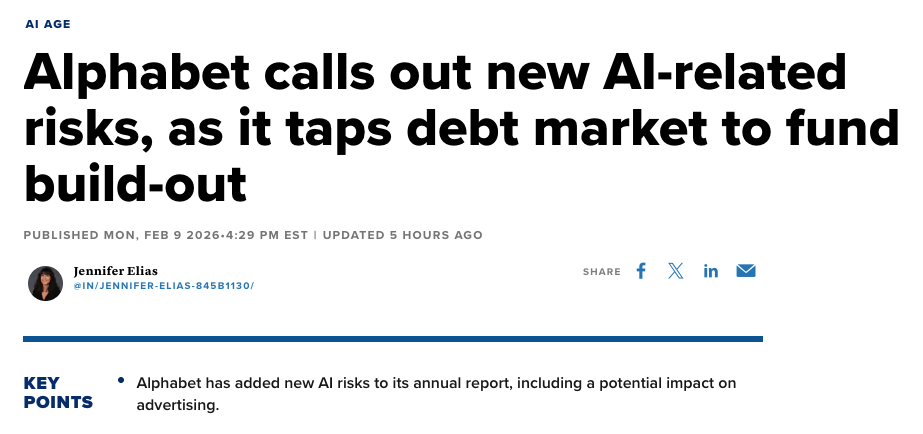

Google is guiding towards $175B to $185B in Capex – as they tap debt markets.

But think about the second order consequences…

Even if those dollars sit primarily with hyper scalers – the implication ripples outward.

Competitive parity may require heavier investment.

Data, compute access, integration layers — these are not free.

What if software becomes less asset-light? What if more high-performing chips and infra are needed to compete?

If reinvestment requirements rise, returns on capital fall.

If returns on capital fall, justified multiples fall.

Therefore, can we still confidently pay a 30x to 35x EV/EBIT multiple for these stocks and expect the same returns?

Or even worse – 40x its free cash flow – as they make these bets?

Up until this year the answer (for most people) has been yes.

But given the lack of adoption the past three years – investors are right to ask these questions.

Questions to Ask

I don"t pretend to know how investors will fare from paying 35x earnings or 40x cash flow for these companies in the years ahead.

I am reasonably confident AI is here to stay.

But what I cannot predict with any confidence is the unit economics.

For example, when you buy or invest in a business – ideally you can predict its cash flows at least 5 years into the future with a strong sense of confidence.

That allows you to value the business.

Sure, it might be considered a high-quality business – but value is another question.

This is now very difficult to do with these names.

However, we can ask questions to challenge some of our blind spots (and there are many):

- If AI lowers barriers to entry, do competitive moats shrink? This is important because if their moats shrink – margins will decline.

- If customers achieve productivity gains, will they share them with vendors or demand lower prices?

- If automation reduces labour needs, does demand for software licences fall with headcount?

- If AI firms must spend more to stay relevant, are today"s margins overstated relative to the future?

- If market leadership broadens, will passive and quantitative flows amplify the rotation?

These are large structural questions (and not intended to be exhaustive).

The answers may help determine how long the cash-generating business models of the past decade will last.

Or will AI turn out to be a cash furnace?

If Charlie Munger were looking at this problem – he would likely avoid the sector entirely.

He would not be able to forecast the cash flow the next 5-10 years with any degree of certainty. However, one thing Charlie taught us to do was always invert.

For example, instead of asking why something should work, he asked how it could fail.

So let"s invert what we find today…

For investors to be disappointed, it would require that:

- AI commoditises capabilities faster than companies can differentiate (a trend we are witnessing already);

- Pricing power erodes as alternatives proliferate (e.g., MSFT"s 3% adoption after 3 years);

- Capital intensity rises while growth rates normalise ($200B capex from AMZN)

- The market continues paying peak multiples for sub-peak economics (eg 40x cash flow; 35x EV/EBIT)

Is that impossible? No. Is it certain? No.

But the probability is higher than it was a year ago – and markets adjust to probabilities, not certainties.

Putting it All Together

I"m a believer in AI long-term.

I"ve worked in the space since 2016… when I worked with Google exploring the use of computer vision.

We felt it was the next evolution of search (i.e., search what you see)

I then moved into scaling virtual twins – which is now useful in train machines to better think like humans do.

And this work at Google continues…

However, as an investor I remove my "engineering hat"– where I separate technology adoption from value capture.

They are not the same.

Part of this requires me to closely scrutinising reinvestment needs.

Businesses that must spend heavily just to maintain their competitive position deserve different valuations from those that can compound with modest capital.

For example, Apple has proven itself to be a business that compounds with very little capital.

Coca Cola is another.

I also pay very close attention to customer bargaining power. Productivity revolutions rarely leave supplier margins untouched. I think this is something Microsoft is going to have to monitor.

In closing, markets are beginning to test whether extraordinary profitability in parts of technology is as durable as what they once were.

Some companies will win this game. But the majority will surprise to the downside.

And whilst reassessment periods may feel uncomfortable – they are also healthy.

What you will find is price discovery improves.

Capital allocation becomes more discriminating. And from that process, the next generation of long-term winners usually emerges.

Remain patient.