Borrowing Costs Are Going Up

Words: 974 Time: 4 Minutes

- Borrowers of all types are going to pay a lot more for debt

- Japanese bonds plunge – as yields rip higher on borrowing fears

- Don"t count on the Fed to cut rates anytime soon

Question:

Can the stock market significantly advance with bond yields going higher?

That"s what investors are trying to gauge.

As governments around the world look increase their (already high) levels of borrowing and spending — it"s plausible bond yields are set to rise further.

And it"s not hard to explain why… demand is falling as supply increases.

But at what point does the stock market say enough?

Governments to Pay Up

The short version of this missive is this is going to hurt.

That"s what the bond market is telling us.

With the US 30-year yield hovering around 5.0% (testing 5.15% last week) – and the US 10-year trading ~4.50% – governments (worldwide) are going to have to pay up for excessive debt.

A J.P. Morgan survey this week said fears are rising.

The poll"s all-client category for outright short positions—which includes central banks, sovereign wealth funds, real money and speculative traders—has climbed to the most since around mid-February.

Fueling that doubt is the US losing its last top credit score, passage in the House of a spending bill that would add $3 to $4 trillion more to an eye-watering $37 trillion national debt (with GDP (output) only $31T)

In addition, we have seen a massive selloff in Japan"s long-term bonds – sending their yields to the highest level in years.

Why the sharp rise in yields you ask?

Reuters told us the 40-year "super-long" JGB yield spiked to a record 3.675% last week as worries about the increase in debt load on their government.

Super-long JGBs lacked the support of traditional buyers like life insurers and pension funds, who have been scaling back purchases.

There"s just one problem:

Governments are looking to bond markets to soak up all this debt.

And unfortunately for governments – the compensation investors receive is simply not enough.

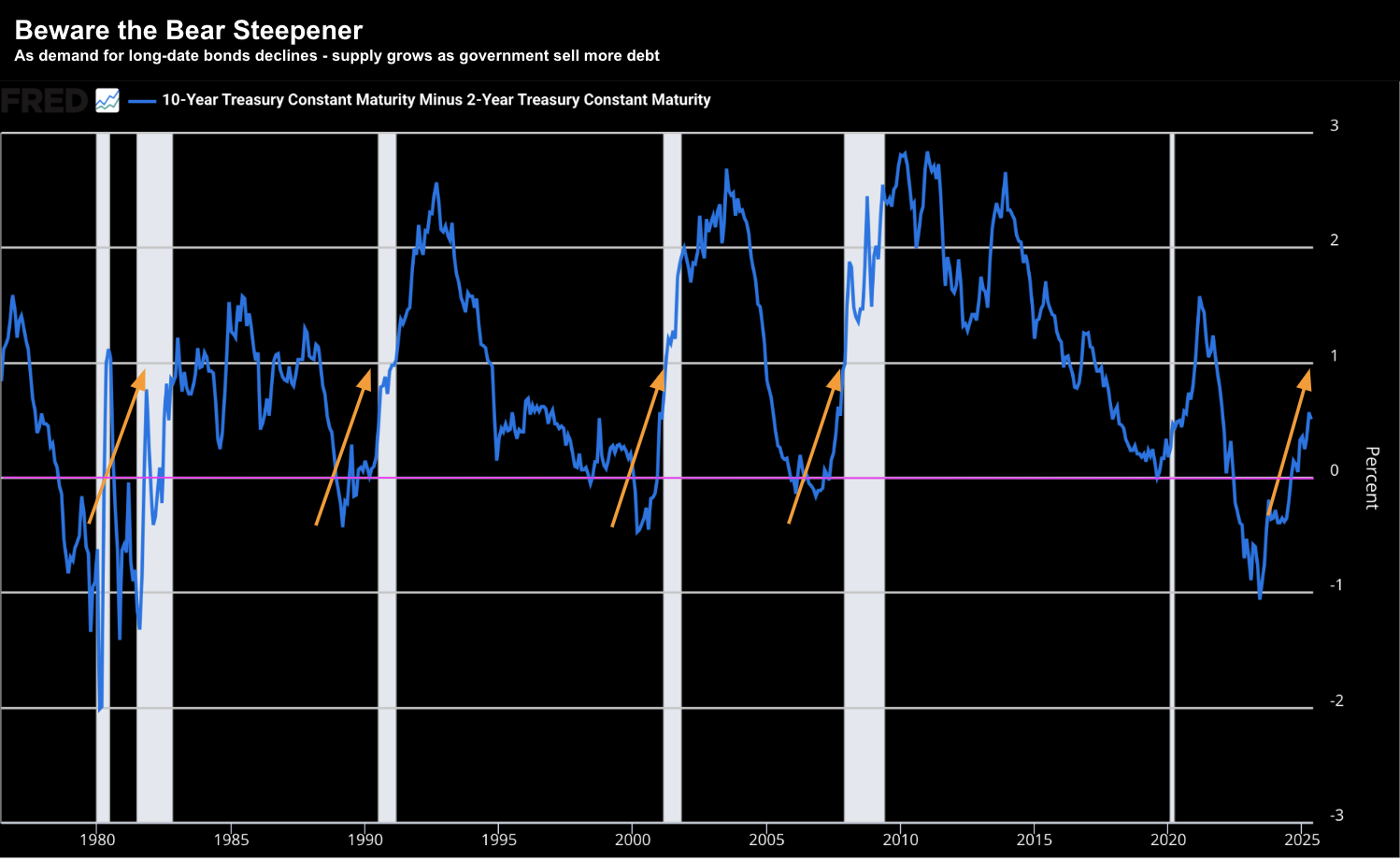

With the long-term yields rising – and central banks looking to lower short-term rates – this is causing a dramatic (global) steeping of the yield curve.

Put another way, as demand diminishes we"re watching supply grow.

That"s going to put pressure on the long end of all these curves (which is not a good thing).

Below is the US 10-year yield less the 2-year (as a proxy for shorter-term rates)

In every instance from 1980 – when the 10-year less the 2-year re-steepened from a negative value (orange arrows) – we have seen a recession result within approx 12 months.

For now the equity market is paying little attention – rallying back to near all-time highs.

But that could be a mistake…

For example, with all borrowing costs already high (and rising) – this will constrain growth.

Not only will it limit what governments can borrow and spend (which is never a bad thing); it will also limit what leverage we see in the private sector (i.e., consumers, businesses, etc etc)

For me, that"s a headwind.

Fed to the Rescue?

With borrowing costs rising – how long before we see the Fed act?

My take – don"t expect anything until Q4.

And for that – look no further than the actions from Trump.

He"s effectively removed any optionality that Powell had to (potentially) help the economy.

For example, in previous posts I"ve talked about how the Fed has been forced to adopt a "wait and see" approach given Trump"s tariffs.

Repeating some language from three weeks ago:

Powell was quick to dismiss the idea of taking preemptive rate cuts as inflation is still running above target saying:

"It"s not a situation where we can be preemptive, because we actually don"t know what the right responses to the data will be until we see more data"

What we now see is a reactive Fed (vs one which would otherwise be proactive)

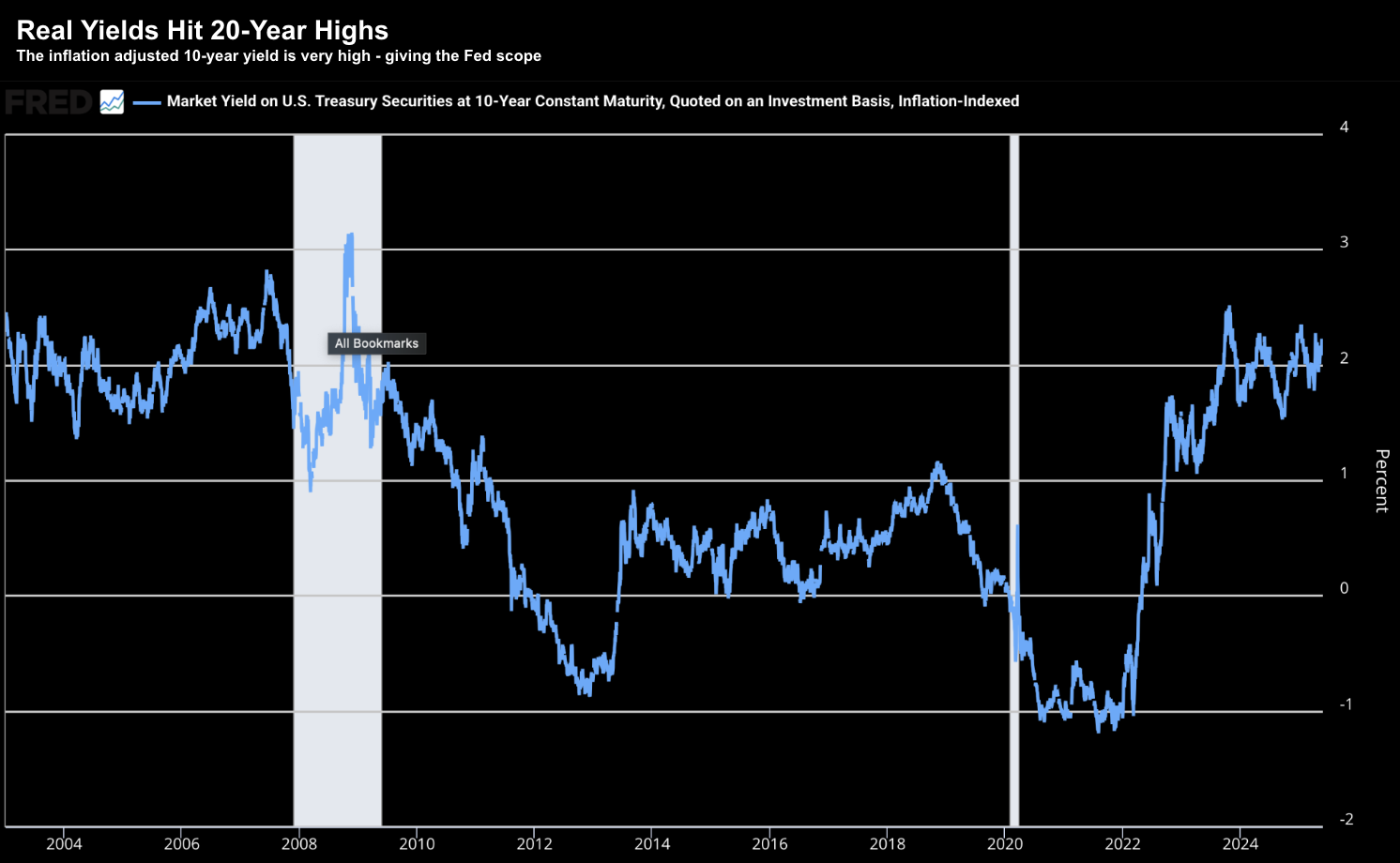

However, without the tariff risks, the Fed could plausible cut for three reasons:

- Economic growth is clearly slowing;

- The Fed Funds rate is still above 4.0%; and perhaps most important

- Real yields remain very high (i.e., nominal rate less inflation)

And to that end, only when we have seen the impact of the tariffs "pass through" (or normalize) – can we be more confident the Fed can resume its cut rates.

But not before.

Putting it All Together

A combination of widening deficits, greater debts, potential fiscal stimulus, and higher inflation isn"t friendly for the bond market (or lowering borrowing costs).

The sum of these suggests longer-term yields are likely to remain at uncomfortable levels.

And perhaps at least one of these needs to reverse course for yields to drop.

That has broad implications for not only the government – but also consumers.

If yields continue to rise – it means all borrowing costs rise.

This includes the cost of your mortgages to car loans to small business loans to credit cards.

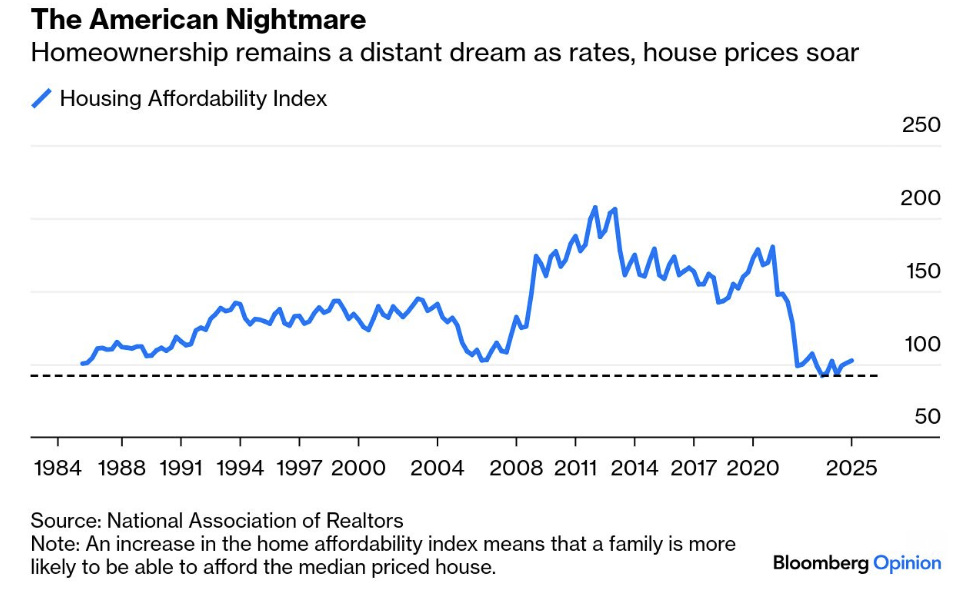

Consider US housing:

Mortgage rates remain relatively high, near 7%, despite the Federal Reserve"s cuts last year.

In addition, the National Association of Realtors" Housing Affordability Index is near an all-time low.

It measures whether a typical family earns enough to qualify for a mortgage loan on an average home, at prevailing rates, prices and incomes.

Sadly for aspiring home owners – they"re going to have to wait.

In closing, bond futures markets are already paring back the odds of rate cuts in 2025.

Traders now only see a 25% chance that the Fed"s first cut comes in July, according to the CME FedWatch Tool—down from 37% a month ago.

My best guess is that the first rate cut won"t come until Q4. However, by then, what damage will be done? Rate cuts at the short-end can only do so much.

For now – equities don"t seem to care.