How Buffett Thinks About Selling

Words: 2,576 Time: 10 Minutes

- A framework to help when deciding to sell

- How Buffett chooses to sell (including examples)

- A new chapter in my journey… leaving Google

With the S&P 500 trading close to record highs – with valuations not seen in decades – do you sell or reduce your positions?

And if you decide to offload some stocks – what positions (if any) should you keep?

I get that question more than any other.

And it makes sense – as selling stocks is much harder than buying them.

For example, just over a year ago I shared this post "Buying is Easy – Selling is Hard"

But it"s a process that every investor should be mindful of.

I explained that a bad investor will end up giving back the money they earned to the market.

Over time, their wealth will be transferred to the good investor.

On the other hand, a good investor will typically keep much of what they make.

They concentrate a lot more on not losing money (vs making it).

But before I share more on how to think about selling and the considerations you should make… I have some important news.

My Next (Life) Chapter…

This week was my last week at Google.

After almost a decade working in the US with the Search giant in the fields of computer vision, machine learning, augmented reality and more recently – Generative AI – I made the very difficult decision to return home.

Unfortunately I could not do my (global) role from Australia.

Over the past few years this decision has been in the back of my mind – but it was hard to "pull the trigger".

I say that because Google is one of the best companies you could hope to work for – leading the way in technology – bound to transform people"s lives and accelerate human ingenuity.

I feel privileged to be part of that for so long – something I will look back on fondly.

But beyond the career opportunity itself – it"s also hard saying goodbye to dear friends and colleagues. And as much as I loved working abroad – family will always be my north star.

Now a new chapter begins…

What that involves I still don"t know. It may involve staying in leading-edge tech (like GenAI) – or something completely different.

However, I"m excited about what conversations and opportunities are ahead – irrespective of the industry.

For example, I"ve been asked if I"m interested in joining the boards of two start-ups (one is tech) — but those are the types of conversations I will be entertaining.

In the short term, I"m doing a large renovation on a house in central Victoria (very close to my parents). That will also keep me "off the streets" for a little bit.

But it will be nice to be home – with family – whilst also creating space for reading, learning and sharing.

With that – let"s talk more to how investors should think about the process of selling – drawing on a framework from Warren Buffett.

A Framework for Selling

Warren Buffett is someone I admire – both as an investor and how he lives his life.

The 95-year old built his immense fortune by identifying and holding great companies that exhibit:

- very strong free cash flows (FCF);

- consistent high returns on invested capital (ROIC);

- strong competitive (lasting) advantages;

- exceptional management;

- buying at very attractive valuations (e.g., low P/FCF and/or low EV/EBIT); and

- selling when those companies were no longer considered attractive.

I"ve spent a lot of time explaining the first five points (see this post). However, knowing when to "cash in" is equally as important.

According to "The New Buffettology" (an excellent read) – Buffett sells his holdings in four key situations:

- When stocks become overvalued relative to bonds: Buffett compares a stock"s expected ten-year earnings to what the same money would earn in bonds. If bonds offer a higher return, the stock is considered overpriced, and selling is a rational choice. The provided example of Coca-Cola in 1998 illustrates how a bond investment would have more than doubled the income compared to holding the overvalued stock. Also see this post on equity risk premium where I explain this comparison (and the risk/reward owning stocks)

2. When a better opportunity emerges: Buffett is willing to sell an underperforming or overvalued investment to redeploy capital into a more attractive company, though he cautions against "selling flowers to buy weeds." He only sells to upgrade to a truly superior business, a rare occurrence that highlights the importance of patience and holding onto great companies.

3. When the business fundamentals change: Buffett sells when a company"s competitive advantage is at risk due to shifts in the industry or poor management decisions. His sale of Freddie Mac is a prime example; he exited the position when the company moved into riskier commercial mortgages, a business he no longer understood

4. When a predetermined price target is met: This applies to investments with a specific, calculable exit point, such as arbitrage situations or corporate conversions. Buffett"s investment in Tenneco Offshore, a natural gas company that converted from a corporation to a partnership, is a perfect example. He bought the stock at a low price based on the future value of the partnership and sold it for a quick profit once the conversion was complete.

With that – let"s explore this framework in more detail… which may help you in your decision to either:

- take profit or reduce exposure to a winning position; and/or

- let go of an underperforming asset – where your capital could be deployed better elsewhere.

#1. Stocks Relative to Bonds

Buffett uses a simple calculation to determine when stock prices become too high. There are two steps:

- Estimate the company"s total per share earnings for the next 10 years.

- Calculate what you would earn if you invested in bonds instead (typically a much safer bet).

If the bond investment would produce more money over those ten years, the stock is overpriced and selling makes sense.

Coca-Cola (KO) Example

- In 1998, KO had earnings per share of $1.42 and had grown earnings consistently around 12% annually for the previous decade.

- Based on this growth rate, an investor holding Coke for ten years could expect the stock to generate ~$24.88 in total earnings.

- In 1998, Coke traded at $88 per share – which meant paying 62 times its annual earnings.

- Therefore, an investor paying $88 for Coke stock would receive $24.88 in total earnings over 10 years (which completes step 1)

- From there, Buffett would calculate what return he would enjoy if investing that same $88 into corporate bonds yielding 6% per year,

- This would be the same as $5.28 per year – totaling $52.80 over 10 years.

Question: as an investor – would you rather earn $24.88 or $52.80 on your $88 investment?

It"s a no brainer!

The bonds would produce more than double the income, making Coke extremely overpriced at 62x its earnings.

Put another way, to justify Coke at 62x its earnings, it would need to grow its $1.42 earnings by 30-40% annually to match the (near) risk free performance of the 6% bond.

Alternatively, the bond yield would need to be between 3-4% (vs the 6% which was on offer)

But as our old friend Charlie Munger would tell us – let"s invert the model and evaluate the risk/reward which stock prices are lower.

For example, let"s now assume Coke was trading at just $28.40 per share or 20x its $1.42 earnings.

That $28.40 in bonds would generate only $17 over 10 years ($28.40 × 0.06 = $1.70 per year × 10 years) — which makes the stock more attractive.

#2. A More Attractive Opportunity

Sometimes an opportunity will come along which is more attractive than the one you are holding.

It could be a stock which is not delivering the cash flow or earnings you expected; or there has been a transformational shift in the business.

Therefore, you should ask whether having your capital tied up in that specific stock (or asset) makes sense?

Buffett will often exit positions when more attractive opportunities emerge.

However, he is also very careful of "selling flowers to buy weeds" (an expression coined by legendary fund manager Peter Lynch)

In short, if you own a "flower" – i.e., a company with a durable competitive advantage and skilled management – then hold it until the market offers an extremely high price.

Short-term price swings shouldn"t concern you when you own a great business – as it will still be generating great free cash flow and generating high returns on its capital (the two key metrics that Buffett prioritize above any other)

As regular readers will know, you should ignore the wild (mood) swings of Mr. Market if the fundamentals of the business has not changed (see this post for a reminder)

Consider this:

- Buffett built his wealth by holding very high quality stocks for long periods (sometimes more than 20 years). From there, compound growth did its thing; and

- He knows switching between investments too often destroys returns, even when new opportunities look appealing.

For example, consider the gradual accumulation of Buffett"s position in Apple from 2016 — where he started buying at a price of ~$23 when its earnings were ~$2.30 – forward PE of just 10x).

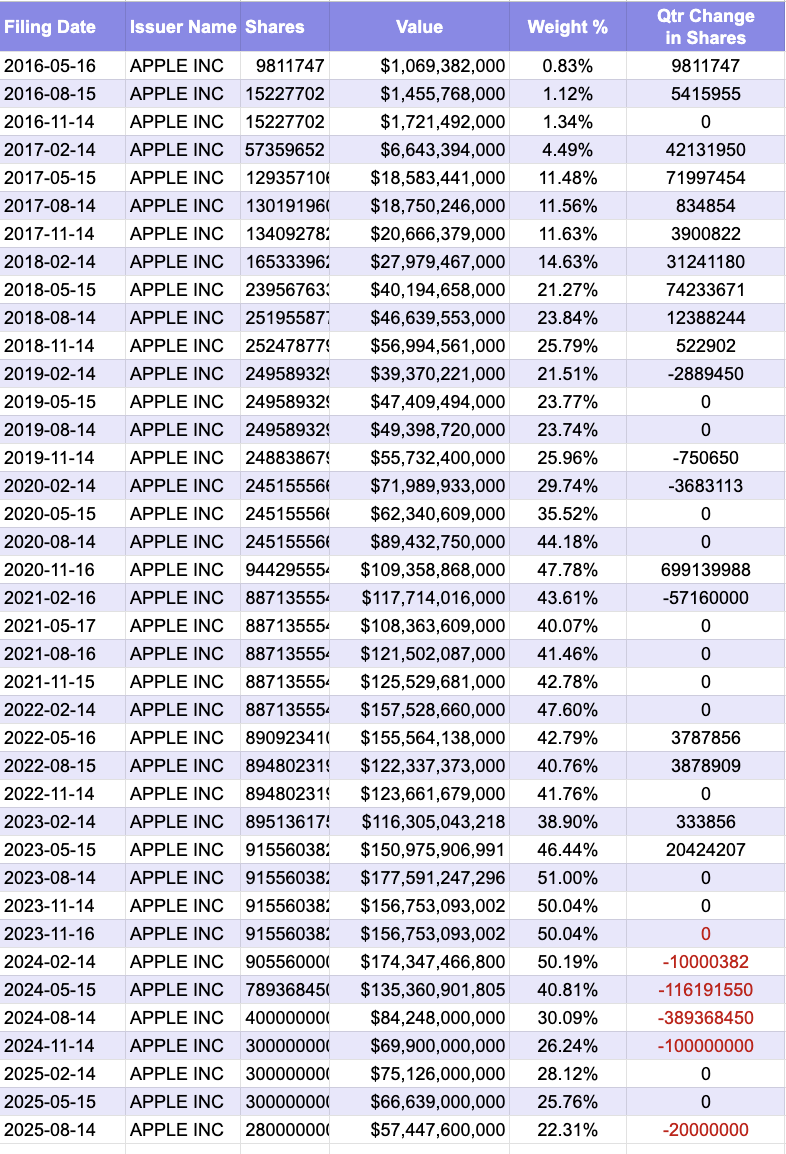

Source: Berkshire Hathaway 13F Filings – SEC EDGAR

** the large increase in shares on 2020-11-16 was due to the 4:1 share price split.

** I"ve written a python-based program which automatically scrapes all 13F filings as they"re submitted; in turn calculating any quarterly change in shares; estimating average purchase (and sale) price; fund performance; and relative portfolio weighting

When Apple started trading above 33x its forward earnings towards the end of 2023 – Buffett started to meaningfully reduce the position.

From the start of 2024 through to his latest 13F filing – he has reduced the position by over 635M shares (i.e., where Apple"s weight has gone from 50% of Berkshire"s holdings to around 22% today).

It"s also worth nothing Buffett"s average purchase price when we accumulated Apple"s stock was about $37 per share.

In addition to reducing his position in Apple – Buffett has unlocked (valuable) capital that can be deployed elsewhere (~$365B – his largest cash position ever as a percentage of his portfolio).

Bottom line:

The key is evaluating whether you are getting more attractive returns elsewhere; or chasing the latest trend (e.g., hyped AI stocks)

Since true upgrades are rare, patience remains the best strategy for very high quality businesses like Apple.

However, there will come a time to reduce (or completely sell) even high quality businesses like Apple (at 33x fwd earnings)

#3. When Things Materially Change

Buffett also watches for changes that could transform a durable competitive advantage into something which is more commoditized (or even replaced).

When the economics of a business shift – great companies can become poor investments.

For example, consider the wave of Large Language Models (LLM) now on the market. These include (certainly not limited to):

- OpenAI"s ChatGPT;

- Google"s Gemini;

- Anthropic"s Claude;

- Meta"s Llama;

- Elon Musk"s Grok;

- Perplexity;

- Mistral;

- DeepSeek;

- Alibaba"s Qwen; and

- Microsoft"s Phi.

Again, this list it not intended to be exhaustive (these are simply some of more popular LLM"s available).

Right now investors are paying huge premiums for AI – however you can easily see how this could easily become commoditized very quickly.

I say this because each of these LLMs are all very similar… with no clear differentiation (that I can see).

Therefore, it"s not unreasonable to think these services will become highly commoditized.

Some question to think about:

- How will these models impact existing business models?

- For those scaling in AI chips (to power LLMs) – how will the "hundreds of billions" in capex offset existing free cash flows and ROIC given (see this post for a related discussion)?

- How will each of these be monetized and how successful will these be (how many will survive / which will perish)?

- Can we model free cash flows for the next 5-10 years with any sense of certainty (or accuracy)? and

- What"s to say these companies will not be disrupted again?

When consumer preferences shift or new technology emerges, the impact appears in revenue. And from there, you can see it in margins (i.e., commoditization through a supply glut).

This visibility gives investors time to react before permanent damage occurs.

As an aside, Buffett says it"s almost impossible to spot trouble brewing at banks and insurance companies because of their ability to manipulate reported numbers. This makes financial companies riskier to own.

His sale of Freddie Mac illustrates this principle.

When Buffett bought shares, Freddie Mac securitized single-family home mortgages and sold them to pension funds, a straightforward business.

The company"s government-sponsored status and residential mortgage expertise created its competitive advantage.

Management then expanded into commercial mortgages seeking higher profits. Commercial real estate requires different underwriting skills, involves longer relationships, and carries more complexity than residential loans.

This shift into unfamiliar territory (what I call "diworsifying") changed Freddie Mac from a predictable business into a risky one, triggering Buffett"s sale.

#4. When Targets are Met

Some investments have predetermined exit points based on specific catalysts or valuation targets.

All arbitrage situations fall into this category because they involve buying and selling to profit from a known price difference that will close at a specific time, like when a merger completes at an announced price.

Buffett has also invested in companies converting from corporate form to partnership form.

These conversions create their own type of opportunity with clear exit points, though they"re separate from traditional arbitrage trades.

Corporate Conversions

His 1981 investment in Tenneco Offshore (a natural gas producer) shows how these conversions create valuation gaps.

Tenneco owned a large pool of natural gas and was paying out all proceeds from gas sales to shareholders.

The company planned to convert to a partnership to avoid double taxation:

- As a corporation: Tenneco earned $1.21 per share but paid $0.41 in corporate taxes, leaving only $0.80 for dividends.

- As a partnership: It could distribute the full $1.21 to investors

With treasury bonds yielding 14%, investors valued dividend stocks by dividing the annual dividend by the bond rate.

Tenneco"s $0.80 dividend meant the stock traded at $5.71 per share (i.e., $0.80 / 14%).

However, after converting, the $1.21 distribution would justify a price of $8.64 per share (i.e., $1.21 / 14%).

Partnerships must distribute their income because partners owe taxes on profits whether they receive the money or not.

This forces partnerships to pay out earnings, making the higher distributions reliable.

The market initially ignored the conversion announcement, allowing Buffett to buy at $5.71.

After Tenneco made the conversion, investors realized they"d receive $1.21 annually instead of $0.80, and the stock rose to $8.

Buffett sold for a quick profit.

This type of investment works because the conversion creates a specific catalyst with a calculable price target, making the exit decision straightforward.

Putting It All Together

Selling stocks is often harder than buying them, but it"s a crucial skill for long-term investing success.

Warren Buffett not only knows when to buy and the importance letting compound returns work their magic – he also knows when it"s time to sell.

Based on his 4-point framework – my recommendations are:

1. Have a Selling Plan — A good investor knows when to sell to protect their capital and lock in gains. A selling strategy is just as important as a buying strategy.

2. Evaluate Valuations Against Bonds Before Selling — Use Buffett"s framework to assess if your stock has become overvalued. Compare its potential long-term earnings (e.g., over ten years) to the guaranteed returns you could get from investing the same amount in bonds. If the bond return is significantly higher, it may be a rational time to sell.

3. Avoid "Selling Flowers to Buy Weeds" — Only sell a high-quality company with a durable competitive advantage if a truly superior investment opportunity emerges. Chasing the latest market trend can destroy returns.

4. Watch for Changes in Business Fundamentals – Continuously monitor the companies you own for fundamental changes. Look for signs that the business"s competitive advantage is eroding, such as declining sales or falling net margins; new disruptive technology; or management making decisions that move the company into unfamiliar or riskier territory.

5. Predetermined Targets for Specific Investments — For certain investments like arbitrage or corporate conversions, have a clear exit strategy from the beginning. These investments have a built-in timeline and price target, so be ready to sell once the catalyst occurs and the target is met.

By adopting this framework – investors can avoid giving back their profits to the market and instead build a more disciplined and effective long-term strategy.

With market valuations extremely high by historical standards – I hope this post proves to be timely.