Words: 2,738 Time: 10 Minutes

- Fed Chair admits stocks are not cheap

- A lesson in discipline

- Why this game will test you

In an interview with CNBC last week – billionaire hedge fund manager David Tepper said he’s constructive on stocks because of (upcoming) Fed easing.

Makes sense.

Stocks tend to do well during an easing cycle in the absence of a material economic slowdown.

However, Tepper balanced his view by adding he’s also miserable because of the valuations.

In his view “nothing is cheap anymore”

Warren Buffett – on the other hand – expresses his view on valuations through asset allocation (e.g. is he a net buyer or seller of stocks)?

For example, at the end of the second quarter of 2025, Berkshire Hathaway’s cash and short-term investments stood at a record high of ~$344.1 billion.

In both percentage and nominal terms – this is the highest level of cash holdings in the company’s history – close to 35%.

You can read more on Buffett’s current holdings here.

Apple continues to be his largest position – despite offloading some 20,000,000 shares last quarter (more on this below).

Regular readers will be familiar with my current sentiment on stock valuations (read this post).

They are very expensive at around 22x to 23x forward earnings (which assumes earnings per share growth of 12% next year).

However, that does not mean they’re about to fall anytime soon (echoing Tepper’s point).

For example, stocks could easily rise over the next 1-2 or years… as investor psychology is a powerful force.

Investor emotions (such as fear and greed) is what drives stocks in the short run – not their fundamentals (read this which draws from Howard Marks latest memo)

However, at some point we will experience reversion to the mean (where attributes such debt levels, cash generation, profit margins, return on invested capital come back into focus)

That’s when a sharp correction could catch people off-side.

It’s my view that forward earnings multiples will revert to approx 16x to 18x (at a guess) – which is in the realm of 6x to 7x less than today’s asking price.

For shits and giggles – some back of the envelope math:

- Assume earnings per share (EPS) for the S&P 500 will be ~$280 next year (12% growth)

- If we discount this by 6x (bringing the multiple to ~17x) – that’s fall of 1,680 points

~25% below a level of ~6600

Experienced investors are becoming increasingly mindful of the (growing) valuation risks.

They’ve seen this movie before (often more than once).

However, shorter-term traders are more concerned about missing out what upside remains.

But at what price?

A Lesson in Discipline

In June of this year – I shared a post talking to Warren Buffett’s 60+ year success as an investor.

His average CAGR over this time is close to 20%.

If you had $10K and applied a 20% CAGR over 60-years – it would be worth $29.2M

How does one generate an average 20% CAGR for multiple decades?

It’s not easy.

Throughout his entire career – the 95-year old has a proven history of when to hold and more importantly – when to fold.

And typically – this has meant being a contrarian.

That is, he was buying when there was fear; and selling when there was greed.

One example is his position in Apple.

Buffett has held Apple for 9 years to realize a ~21% CAGR on this position (i.e., entry of ~$37 in 2016 to around $230 today)

But when he purchased Apple – the company was not in favor.

The iPhone maker traded at less than 10x its forward earnings.

Fast forward to today and that multiple is above 33x – still one of the most widely-held stocks.

Now Buffett was fine paying less than 10x earnings for a high quality company; but he is often a seller at 33x.

After sitting on a near 470% gain – he knew that Wall Street was not the safest place to ‘store’ that risk capital.

Buffett appreciates the cyclical nature of markets.

That is, he recognizes there will be long stretches of time when a prudent investor should get out and stay out.

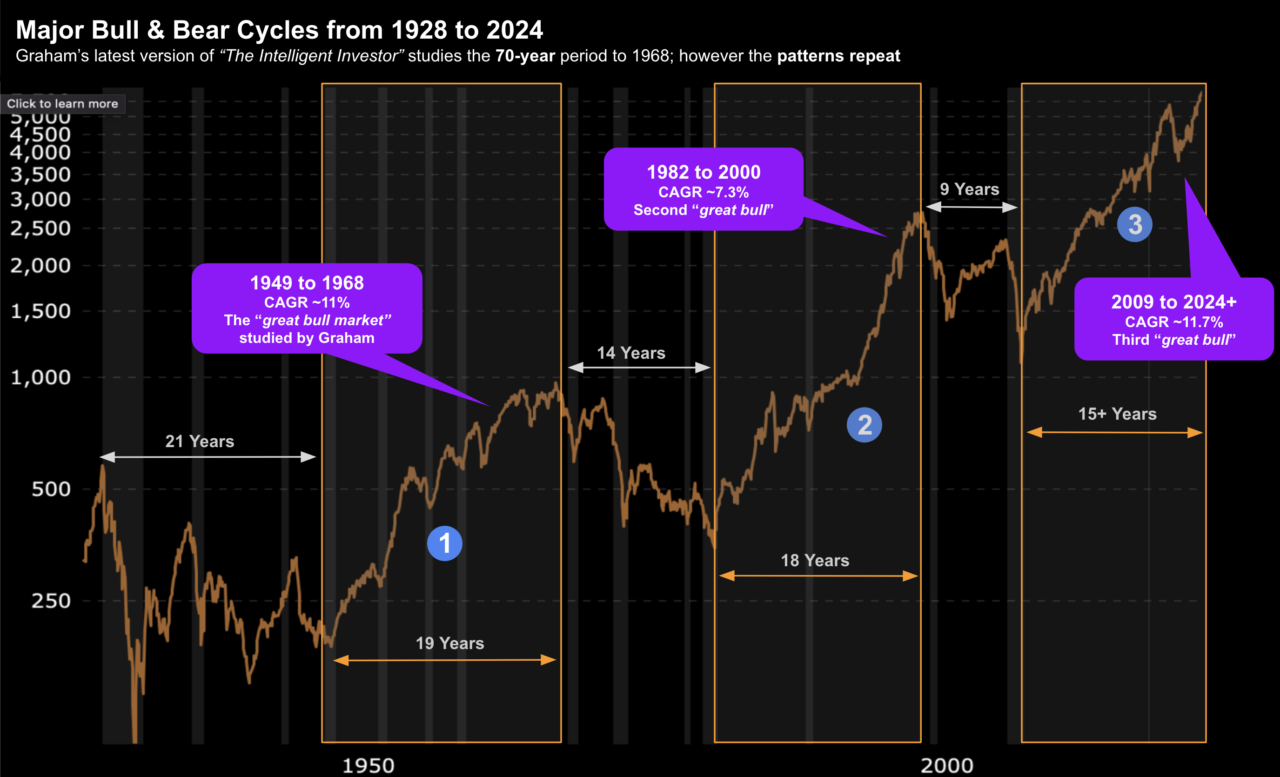

Borrowing from my earlier post in June – I draw your attention to this 20-year span for the S&P 500: 1955 to 1965; and 1965 to 1975.

| Start Date | End Date | Start Value | End Value | Total Return (%) | CAGR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1, 1955 | Jan 1, 1965 | 35.60 | 86.12 | 141.91% | 9.23% |

| Jan 1, 1965 | Jan 1, 1975 | 86.12 | 72.56 | -15.73% | -1.69% |

A 27-year old Buffett launched his professional investment career in 1957, when the bull market that began after World War II was still young.

Fortunately for Buffett – he avoided the nearly 20 years it took to recover from the Great Crash of ’29 (Buffett was born in 1930)

With returns flat to negative for almost two decades – even the most ‘steadfast’ of investors were wary of buying stocks.

But an investor bold enough to take a position in 1948 would find that by 1968 they had more than quintupled their money (see graphic below — a stellar CAGR of ~11%).

The S&P 500 CAGR between 1955 and 1965 was an impressive 9.23% excluding dividends.

It was an extraordinary good period for investors (not unlike today’s epic 15-year bull run from 2009)

Buffett started his first investing partnership in the fifties (before Berkshire Hathaway in 1964)

It was a pool of money for a group of close clients, many of them friends and acquaintances, forming what he called the “Buffett Partnership”.

Over the next decade – he would return a stunning 1,156% vs the Dow 122%.

His 10-year CAGR was an incredible 28.7% vs the Dow CAGR of 8.4%

But here’s the real genius…

Two years before the market peaked in 1968/69 – Buffett realized that a bull this brazen was just asking to be replaced by a bear.

Valuations were simply too high.

Worried that he would not be able to find a safe home for fresh money, Buffett closed his partnership to new accounts.

In 1967 his fund rose 36% more than twice the Dow’s advance. And in 1968 – he returned 59%. Here’s Buffett from his 1969 newsletter:

The game is being played by the gullible, the self-hypnotized, and the cynical

In May of 1969 – he announced he was liquidating the Buffett Partnership – cashing in his chips.

Buffett spent the rest of the year selling stocks so that he could return his investors’ money-plus the handsome profits their investments had accumulated over a period of years.

He advised them that he was putting most of his own money into municipal bonds (at an average yield of around 5.8%), while holding on to just two stocks:

- Diversified Retailing – a small holding company for a dress chain, and

- Berkshire Hathaway – a textile company

- Keeping their Berkshire Hathaway shares; or

- Taking the cash

Being Greedy When Others are Fearful

With Buffett’s cash safely buried in Main Street (and out of Wall Street’s grasp) – he was not seduced by the rallies that followed his exit in May of 1969.

For example, from 1969 through 1973, the market experienced several sharp rallies.

- 1969: The S&P 500 experienced a decline of -15.19%.

- 1970: The market saw a slight recovery, with a total return of 4.01%.

- 1971: The S&P 500 continued its upward trend, with a total return of 14.31%.

- 1972: The market saw further growth, with a total return of 18.98%.

With returns of 14.3% and 18.98% – many would have declared the bear market of 1969 over.

However, despite the strong rallies — Buffett continued to stay out.

Drawing a parallel to today (and the enthusiasm around AI stocks) – he was not tempted by the so-called Nifty Fifty growth stocks.

As a value investor, committed to “buying low and selling high,” Buffett understood that everything depends on the price you pay when you get in.

In that sense, any value investor is a market timer.

At near the end of a cycle, when prices were stretched (and greed was rife) – he used that opportunity to sell.

And in Buffett’s view, in the early seventies prices still were exorbitant.

But it was not until 1973, when the Dow went into free-fall, that the market once again commanded Buffett’s attention. As he told Forbes late in 1974:

“All day you wait for the pitch you like; then when the fielders are asleep, you step up and hit it.”

- Whilst Buffett’s exit from stocks was arguably early – he was not late. After all, if he had hung on, he could have ridden the Dow to the very top: 1071 in January of 1973. Being early is always better than being late; and

- He had the conviction of his own judgement to step up and buy quality assets when valuations were attractive (where very few others could conquer their fears)

What’s the lesson:

Buffett is far more concerned with not losing the extraordinary returns he had made (Apple is a good example).

While most investors are motivated by a desire to make money, Buffett focused first on not losing money.

But compare that to the average investor…

They will agonize over the prospect of missing out on the profits that would have made them rich.

But the very rich don’t fret so much about making money. Their greatest fear is losing it.

Armed with cash – after the Dow had crashed – in 1973 when no one else wanted to buy stocks (or had the ability to!) – Buffett went on a buying binge.

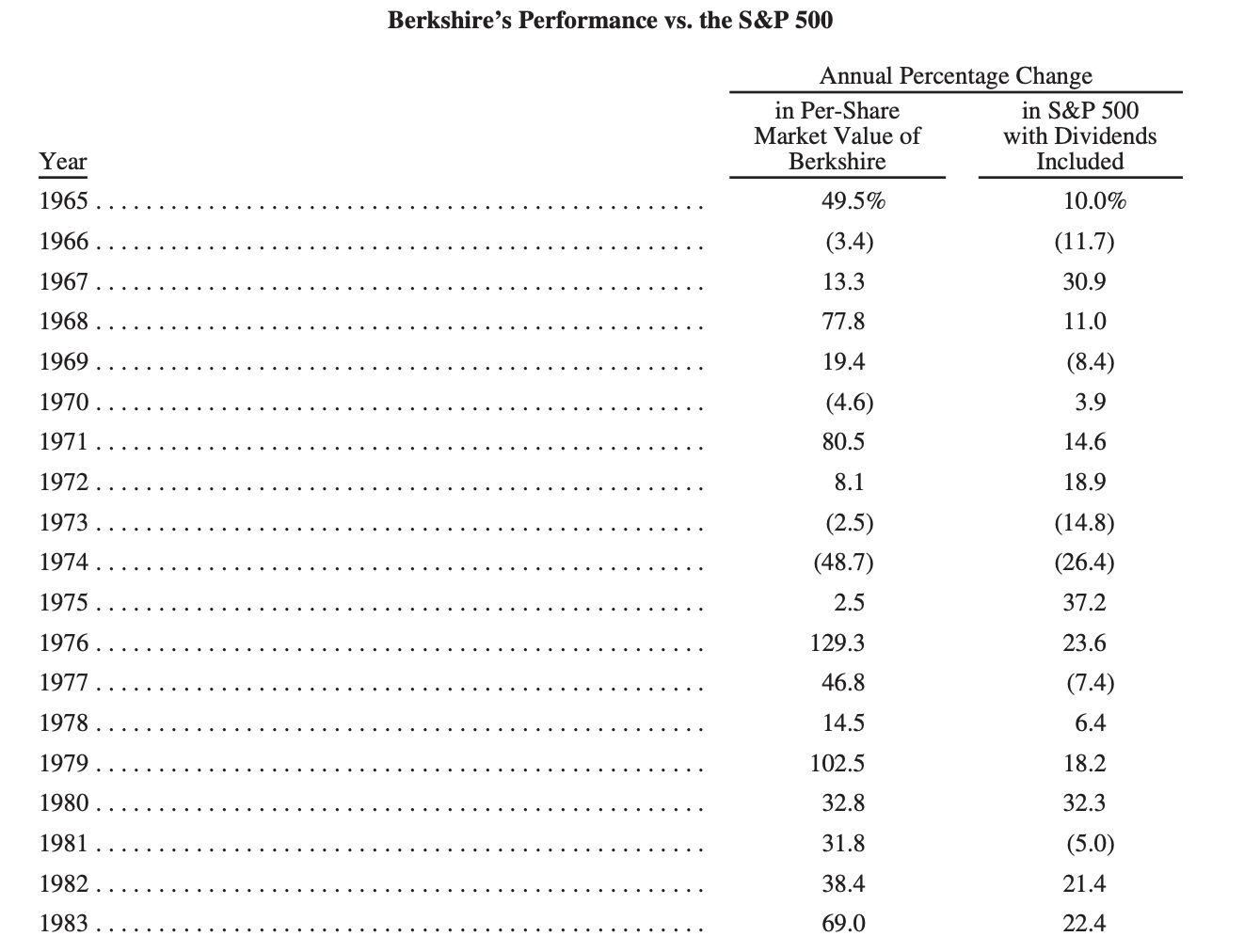

Corporate America was on sale, and Buffett snapped up one company after another at 7x their forward earnings (and sometimes less). Below is the comparison of Buffett’s returns vs the S&P 500 during this period:

Following the crash of 1973-74 – where the S&P lost 14.8% and 26.4% in consecutive years – Buffett capitalized – realizing stellar gains every year between 1976 and 1983 (leaving the S&P 500 in his wake)

Before I move on…

Buffett did something very similar in 1997.

As part of his annual shareholder letter (released early 1998) – he cautioned investors about the “preening duck” syndrome.

This where a duck that soars in a flood mistakenly believes its own paddling skills caused its rise.

He noted that the S&P 500 had performed nearly as well as Berkshire Hathaway that year, and he warned that investors should not mistake a broad bull market for individual skill.

He was also a net seller of stocks that year, a clear sign of his view on valuations.

Needless to say… Buffett was about two years early taking his profits before the dot.com bubble exploded.

Question:

Could 2025 be similar to either 1968 or 1997?

That is, stocks may still run further – perhaps topping 7,000 this year. It’s possible.

However, in ‘two years’ from now, I wonder if we will be looking back at “2025” as the time to take some profit?

Which Brings Us to Powell…

Anyone who traded through the ~50% declines of 2000 and 2008 will be wary of the risks.

I was crushed in the year 2000… which I fondly call my “market tuition fees”.

You pay to play this game.

That cost will either be (a) capital losses; and/or (b) the time it takes to learn how to invest.

But I consider myself lucky – as I learnt life-long lessons before the age of 30.

Put another way, I would hate to make those same mistakes at the age of say 40 or 50 (as you have far less time to recover).

Time is our greatest asset.

Now if you were born before 1950 (like Buffett) – there are not many new things under the sun.

Jay Powell – born in 1953 – has also experienced his share of economic cycles.

Today the out-going Fed Chairman shared a few words on market valuations.

Singing from the same cautious hymn sheet – he too noted that asset prices are at elevated levels.

During a speech in Rhode Island, the central bank leader was asked how much emphasis he and his colleagues place on market prices and whether they have a higher tolerance for higher values.

We do look at overall financial conditions, and we ask ourselves whether our policies are affecting financial conditions in a way that is what we’re trying to achieve,” Powell said. “But you’re right, by many measures, for example, equity prices are fairly highly valued.”

“Markets listen to us and follow and they make an estimation of where they think rates are going. And so they’ll price things in”

Though Powell noted the lofty equity values, he said this is “not a time of elevated financial stability risks.”

Markets are expensive but financial conditions are stable due to the sheer abundance of liquidity.

You only have to look at the very low level of credit spreads.

However, stability today doesn’t mean we will have stability tomorrow. Things can change very quickly.

For example, if you’ve read any of these three books by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (which I highly recommend) – you will understand:

- Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets

- The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable

- Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder

Every investor should be familiar with these books.

Taleb emphasizes that humans are fundamentally bad at understanding and preparing for randomness.

In most cases, they downplay the risks.

For example, in Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets , he argues that we mistake luck for skill and tend to find false patterns in data (echoing Buffett’s “preening duck” syndrome)

Building on this, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable introduces the concept of an outlier with a high impact that is retrospectively predictable but impossible to foresee.

For example (and this list is not meant to be exhaustive):

- What if we see a currency crisis in Argentina?

- Could the war between Russia and Ukraine expand to other countries?

- What will be the impact of tariffs on global supply chains the nexts 12+ months?

- Are global debt levels and growing fiscal deficits a risk? or

- What happens with a 10-year yield above 6.0%?

There’s a long list of “retrospective predictable” risks where investors remain highly complacent.

Yes, markets are stable today. They were also stable in 1997 and 2006.

I wasn’t around at the time – but my guess is they were reasonably stable (e.g. where stable is said to imply low unemployment levels / low credit spreads / ~3% economic growth) in 1968/69 – when Buffett was liquidating his fund.

What’s my point?

As humans, we tend to have a collective failure to acknowledge the true nature of uncertainty – which is dominated by highly improbable and consequential events.

Putting It All Together

Please don’t take this missive to “sell everything” and hide in some bunker.

Quite the opposite…

David Tepper and Warren Buffett maintain meaningful exposure to high quality stocks.

However, they are mindful of the risks.

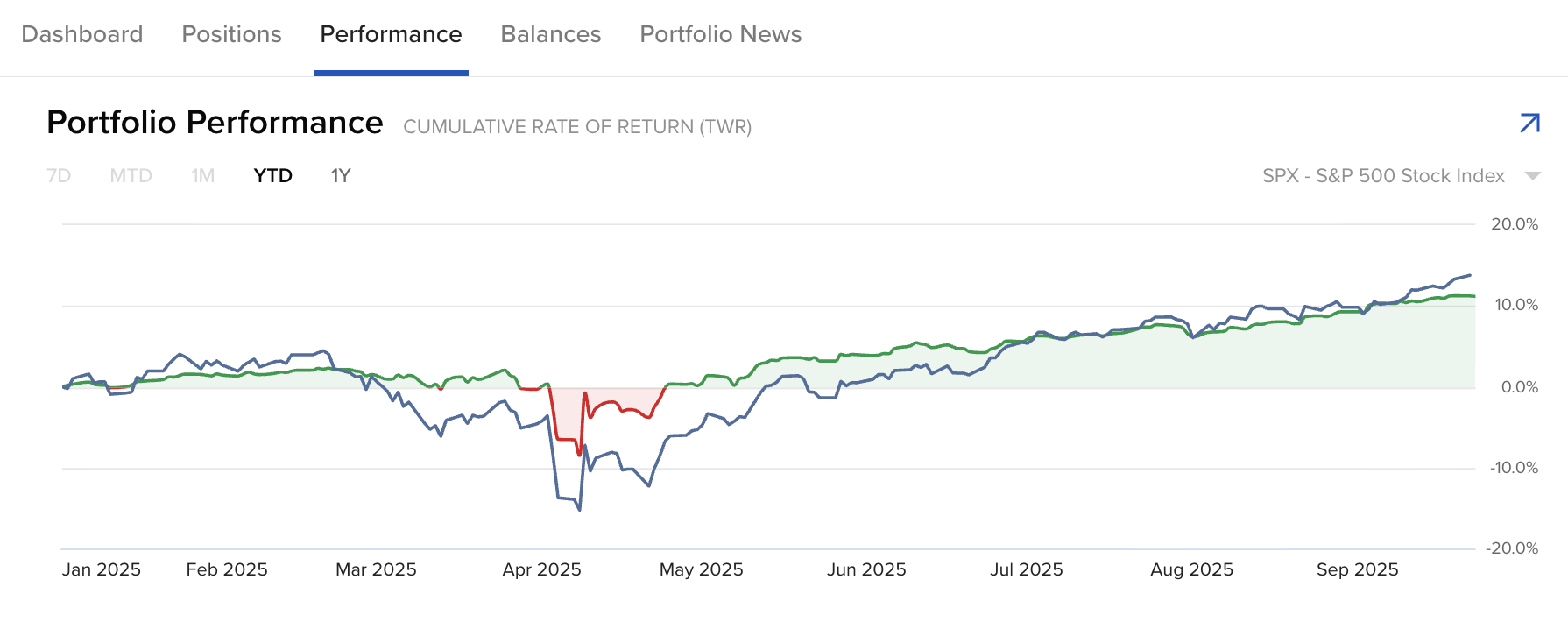

As for myself, I remain ~65% long – with the balance of 35% in cash or cash equivalents.

Ensuring I had (some) exposure to high quality assets (which were purchased at reasonable valuations) – has my portfolio is up ~12% year to date (slightly lower than the S&P 500)

My 9-year CAGR is around 14%.

That said, I also recognize that I often underperform during strong bullish markets (i.e., where valuations are high).

I tend to outperform during bearish markets.

And whilst I’m happy not buying anything today – I have a list of ~50 stocks I would like to buy.

However, none are near the price I would be happy to pay (e.g. on an EV/EBIT or P/FCF basis).

I also have an expectation that it could be “one, two, three” years or more before I am able to buy what I think is an attractive risk/reward.

That’s fine.

But I have a very high confidence level that every few years – along comes a very high quality asset at an attractive price.

That’s when I put my cash to work.

Assuming my diligence is correct on the quality of the asset – typically after a few years the market will correct its mistake and bid the stock higher.

It’s not always the case but generally that’s how it goes.

In closing, whilst the chorus of warnings is growing, it does not mean a stock correction is imminent.

Stocks are likely to rise as the Fed eases.

However, you could do a lot worse than taking a few chips off the table at these prices.