Words: 1,040 Time: 5 Minutes

- Powell can take long (well-earned) summer vacation

- Trump wants rates cuts – he won’t get them

- The dreaded ‘S’ word rears its ugly head

Not for the first time, the Fed is in a very difficult spot.

Whilst always a dominant force in global markets, for now, Powell’s team is not in the front seat.

We learned this week the direction of U.S. monetary policy (over the coming months) depends heavily on developments well beyond the Fed’s control.

And unfortunately for investors – it could be a long (US) summer.

In its latest decision, the Fed held rates steady, as expected, citing strong economic activity, low unemployment, and persistent—but slightly elevated—inflation.

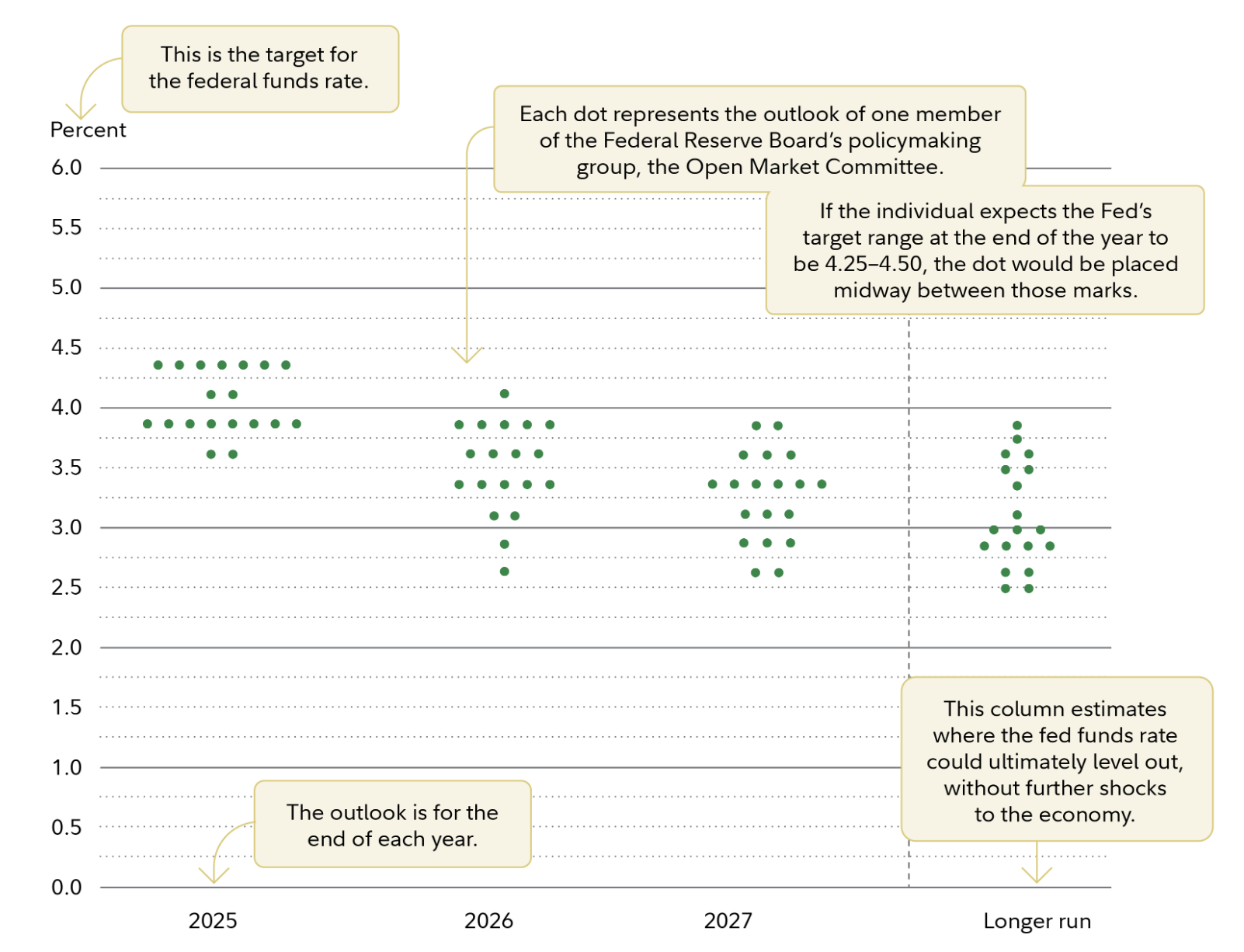

The most market-moving detail was the updated “dot plot,” showing individual Fed officials’ rate forecasts.

While the median still points to two rate cuts later this year, the overall picture hasn’t shifted much since March.

Few Doves in the Plot

- Vertical Axis: Target percent for the federal funds rate.

- Horizontal Axis: This shows 3 years—the current calendar year and the next 2—plus the “longer run.” Each year indicates expectations for the end of that year. The “longer run” column estimates what a “neutral” interest rate might be, which would neither heat up nor cool down the economy.

- The Dots: Each column contains one dot that represents the outlook of one member of the Fed’s policymaking group, the Open Market Committee. If the individual expects the target range at the end of the year to be 4.25–4.50%, the dot would be placed midway between those marks.

A word of caution — take these “dots” with a large grain of salt. For example, Powell reminded participants about their own inability to forecast:

“No one holds these rate paths with a great deal of conviction… and everyone would agree that they’re all going to be data dependent.”

And given what we see with the increasingly ‘fragile’ state of markets (e.g., war in the Middle East and Ukraine, ongoing tariff risks, fiscal policy w/Congress, the coming debt ceiling debate, long-term rates) – these dots could change sharply in a month or two.

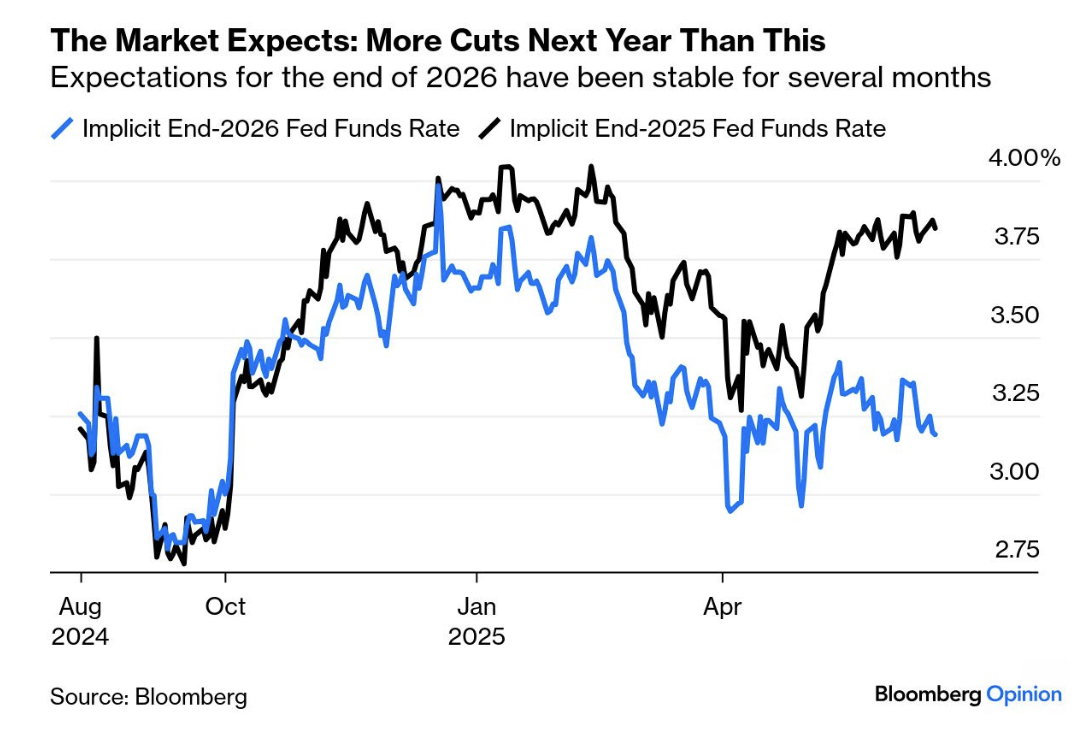

But for what it’s worth – the rates market, as gauged by Bloomberg’s World Interest Rate Probabilities – has consistently predicted that fed funds will be somewhere between 3.0% and 3.25% by the end of next year.

If correct – this implies two incremental cuts vs what the Fed currently predicts — which in turn suggests that traders are more worried about growth than the central bankers are:

The Dreaded ‘S’ Word

On the surface, these are both considered ‘healthy’ – however they are also rear-view mirror.

Looking ahead – which is more important – the risks have clearly increased.

For example, the Fed’s latest projections showed a slight downgrade to next year’s growth and a modest uptick in expected inflation—suggesting a mildly stagflationary outlook.

However, the signals on the next rate move remained largely neutral.

Despite this, markets initially reacted as if the update were dovish, sparking a rally in two-year bonds, which are closely tied to expectations for the fed funds rate.

But that sentiment quickly faded…

Chair Jerome Powell’s press conference, which began just 30 minutes later, pushed back on the market’s optimism—effectively reversing most of the earlier gains in a matter of minutes.

The key moment in Powell’s press conference that pushed bond yields higher came when he addressed the impact of tariffs:

Ultimately the cost of the tariff has to be paid, and some of it will fall on the end consumer. We know that’s coming, and we just want to see a little bit of that before we make judgments prematurely.

Bingo!

Again, to help dimension this risk, the US imported some $3.8 Trillion of goods last year.

If we assume a average blended rate of just 10% (which I think is your best case) – who will pay for the $380B+?

I’m willing to bet business won’t absorb all of it.

This signaled the Fed’s reluctance to cut rates until it’s confident tariffs aren’t reigniting inflation.

As I like to say, Trump has forced the Fed to be reactive vs proactive.

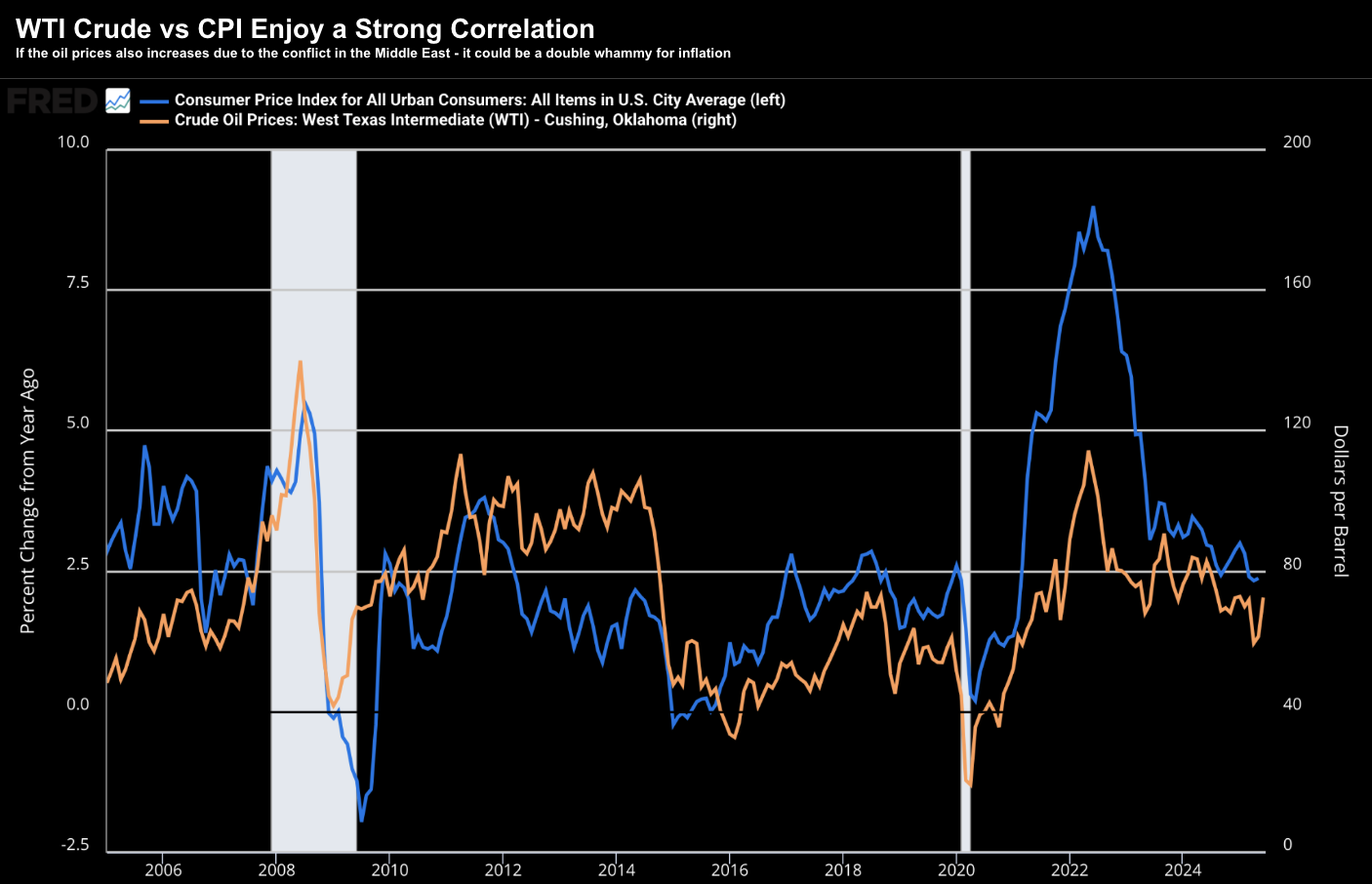

The added uncertainty from Middle East tensions, which could drive up commodity prices (specifically oil), only strengthens the Fed’s case for patience.

For example, Powell’s strong emphasis on price risks, rather than slowing growth, implies he may support only one—or even zero—cuts this year.

That’s not what markets have priced in…

The Misery Index

Something Powell can use as a defense is the so-called “Misery Index”

This is an economic indicator created to measure the level of economic hardship.

It is calculated by adding the unemployment rate and the inflation rate.

The higher the index, the greater the perceived economic discomfort.

And for now – it’s relatively low by historical standards.

For example, with CPI YoY ~2.30% (Core PCE at 3.10%); and unemployment ~4.20% (expected to rise to 4.50%) — the Misery Index is trading around 6.5%

Over the past 50-years – the Index has never fallen below 5% (left-hand axis)

Even in the boom of 2006, it was 5.7%.

However, during times of recession, the Misery Index spikes, driven primarily from a higher unemployment rate with low inflation.

Therefore, one might argue their “defensible position” for not moving on rates is justified (for now)

Putting it All Together

In closing, Powell rarely finds himself on the minority side of FOMC decisions, so if he’s leaning hawkish, investors should pay attention.

That said, the broader message from the Fed remained one of status quo.

The committee carefully avoided making any major policy shifts, and markets got the message.

Until there’s more clarity on tariffs and geopolitical risks, the Fed is content to hold steady—especially with unemployment low, inflation easing, and financial markets performing well.

To that end, I think markets (reluctantly) got the message.

Trump however remains oblivious to the economic risks.