The RBA’s Dilemma… When Things Go Wrong

- Lessons Learned from Down Under

- Rate rises likely to come "thick and fast" from 2022

- Exaggerating the boom and bust cycle

This week we will hear from the Fed on monetary policy…

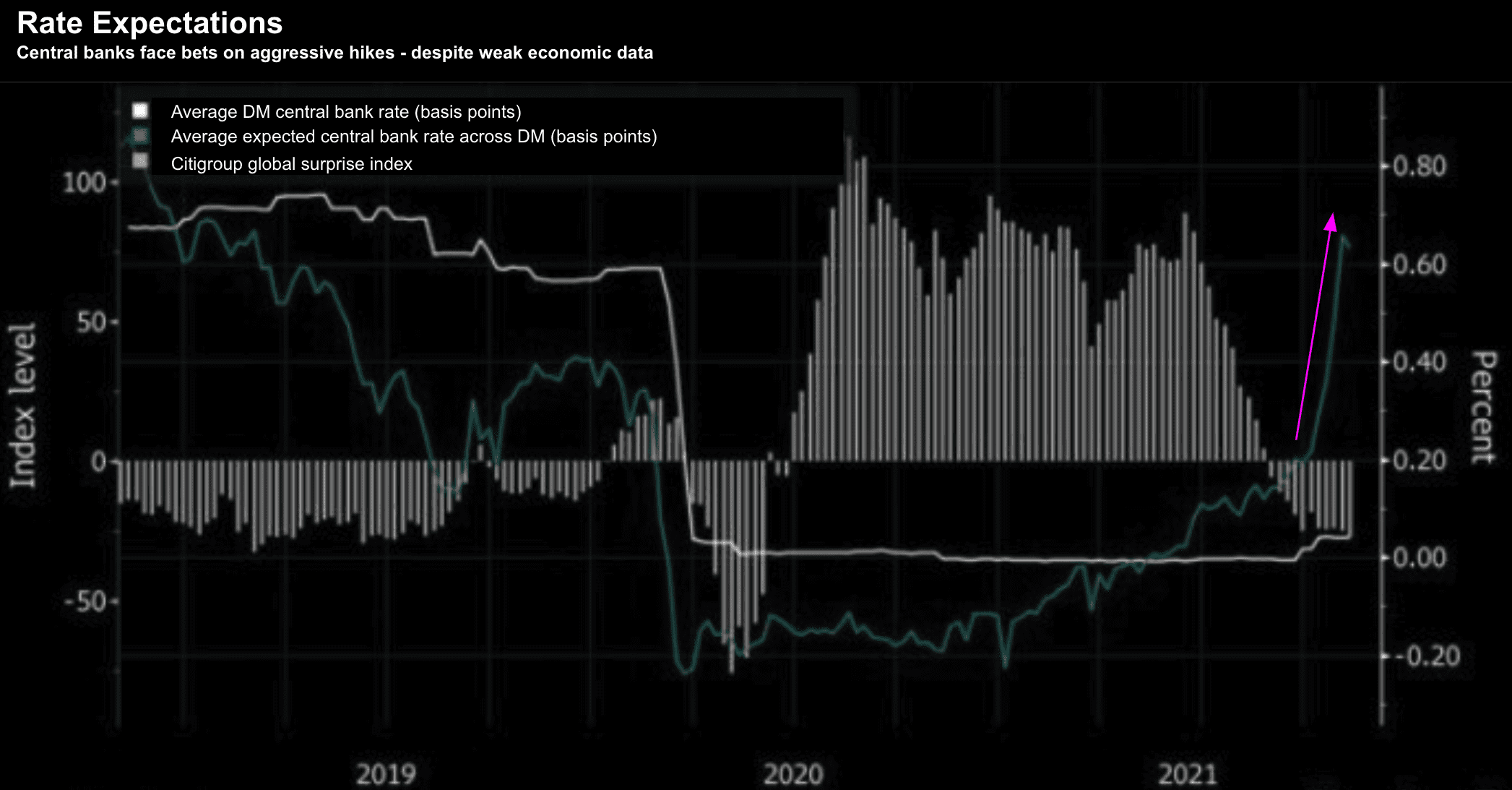

They are expected to not only announce imminent plans to reduce their $120B monthly bond purchases (as early as November) – but are likely to shed more light on their timing of rate rises.

As I wrote recently – I think bond markets (specifically the 2-year) – are already telling us what the "dot plot" will be.

We don"t need a survey of Fed Presidents.

For example, look for rate rises as early as June 2022… vs expectations of the end of 2023 only a few months ago.

But here"s the thing…

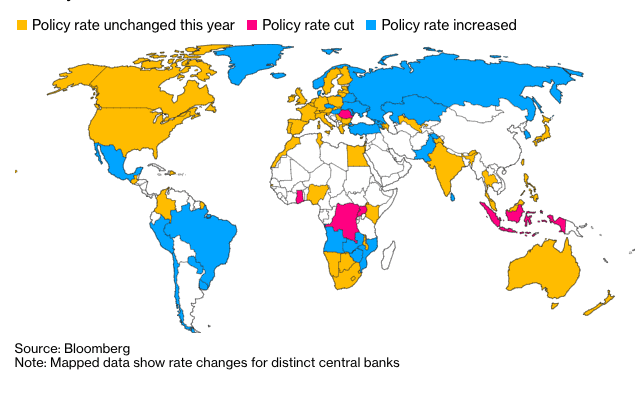

It"s not just the Fed who feel their hand is being forced… this is global.

Whether it"s the Bank of Canada, England, Norway, New Zealand and Australia (more on the RBA shortly) – they are all either starting (or have started) to tighten monetary policy.

Inflation risks are real… and the so-called genie could be "out of the bottle".

But if we zoom out – the great "QE" experiment of 2020/21 is coming to an end (and perhaps about 6-9 months longer than it needed to be)

What we see with money creation was unprecedented…

No-one knew exactly how this was going to turn out… and we still don"t.

But as the thematic map shows below – "the bar tab" is starting to close.

Last drinks?

Here"s my question:

If there"s a cost to this global monetary experiment – what will that cost be?

For example, will it be in the form of sustained unwanted inflation (where excess money is chasing too few goods?)

Maybe it"s stagflation; i.e. where we get very low growth with inflation (weighed down by record levels of unproductive debt)?

Or perhaps one massive misallocation of capital (e.g. higher stocks and houses) – resulting in an exaggerated boom / bust cycle?

Who knows… maybe all three… or something else entirely.

Sooner or later everyone sits down to a banquet of consequences (Robert Louis Stevenson)

But let"s take a look at what"s happening "down under"…

Very few developed markets (DM"s) have speculated as much into property over the past 12 months as Australia.

It"s what I like to call a "poles and holes" economy…

That is, money comes from digging up "red dirt" and "fossil fuels" to sell to China ("holes")… which is then leveraged against housing ("poles").

It"s a shame – as "poles" it"s not a good use of productive capital.

It"s speculative.

In any case, this works (in part) with two necessary conditions:

(i) rates remain low; and

(ii) revenue keeps coming in (i.e. China continues to buy)

But both of these are at risk…

Let"s talk to rates…

Property Storm Clouds Gather

"Hand someone "cheap" money… and they will generally take it"

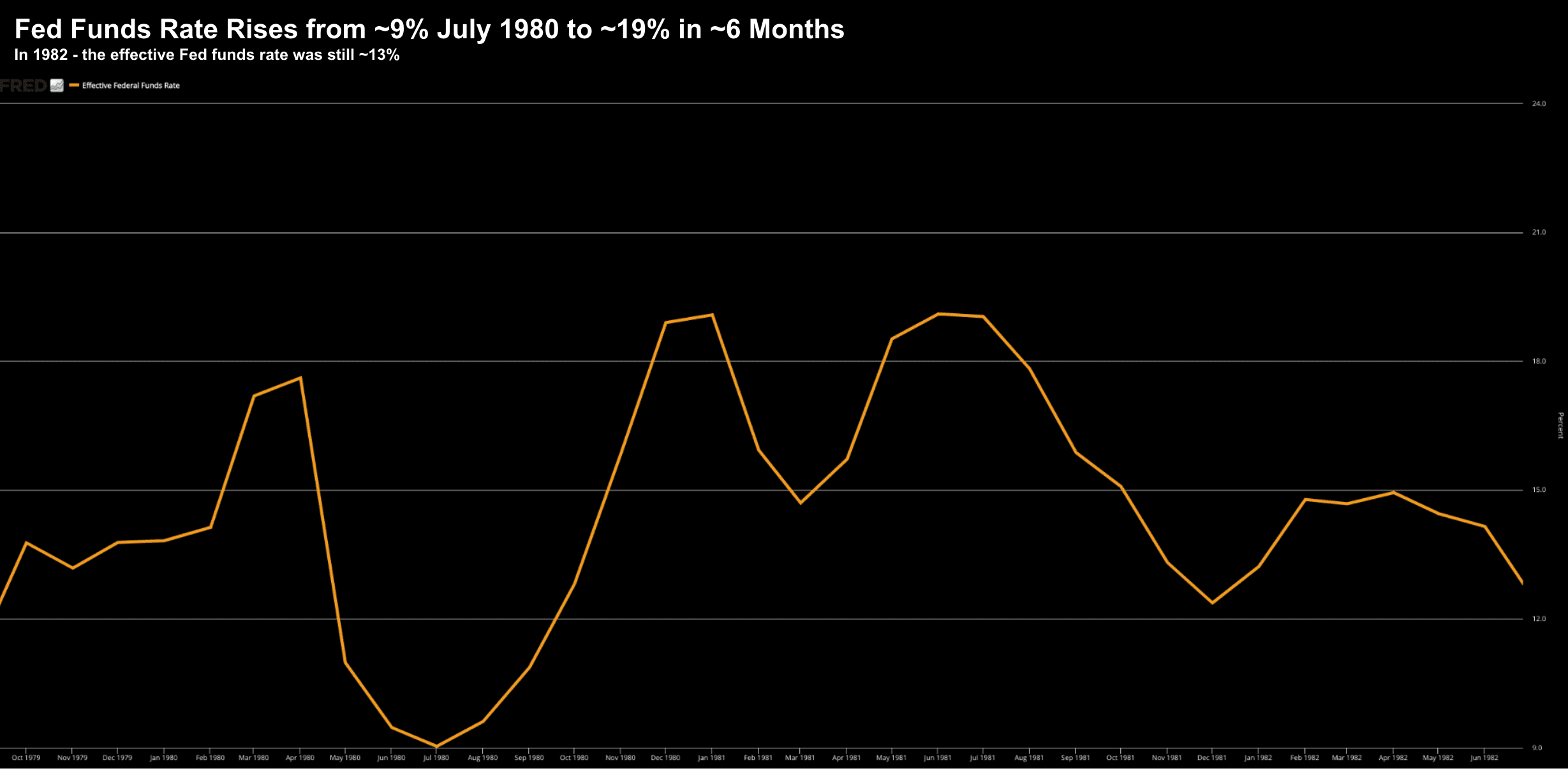

That"s paraphrased from former US Fed Chair Paul Volcker… who resided over 18%+ inflation rates in the late 70s / early 80s.

Volcker had only one option… hike rates and fast.

For example, he raised rates from ~9% in July 1980 through to around 19% in just 6 months.

When Rates Jumped to 19% to tame Inflation

Now I don"t believe for a second we will see "19%" rates anytime soon (if ever).

In fact, rates won"t have to get that far to cause financial devastation.

For example, an effective cash rate at 8% (at a guess) would probably have the same effect.

Why?

The amount of debt in the system.

That"s the big difference between 1980 and now.

Whilst not the focus of this missive… consider this quick parallel.

- In the 1980s, on average, Australian"s paid ~3x their annual income to buy a house.

- Fast forward to 2021 – that ratio is around 6-8x (10x in extreme cases)

Borrowing 6x your annual income doesn"t work at 19%. It doesn"t work at 10%.

But what have we seen with speculation in Aussie housing?

Here"s some numbers from the Australian Financial Review article (October 2021):

"Unsustainable debt trends could emerge in an environment of rapidly rising property prices and extrapolative expectations, with new borrowers stretching their financial capacity and a greater chance of disorderly future price corrections."

Over the past 12 months, home prices have increased by an average 20.3 per cent across the nation, with the biggest increases seen in Hobart (26.8 per cent), Canberra (24.4 per cent) and Sydney (23.6 per cent).

More relevant to regulators" concerns, over the same period, the average owner-occupier home loan grew by 15 per cent to $564,900.

In NSW, the lift since February was $112,000, pushing the average loan to a record $732,000.

The average annual income for an Aussie is said to be $90,000

Quick math:

- If the national average home loan is $564,000 – that"s 6.3x avg. annual income; and

- For NSW specifically – at an average of $732,000 – that"s 8.1x avg. annual income

Personally, I can"t fathom borrowing anything close to 6x your income.

3x my income terrifies me.

Last weekend, AMP Capital economist Shane Oliver said the Aussie housing boom is likely to end the year with ~21% YoY gains.

He added that low mortgage rates, an ongoing relatively low level of homes for sale and a resumption of economic and jobs market recovery after the lockdowns point to further home price increases ahead for a while yet.

However, looking beyond the next 2-3 months, he offered this:

"Storm clouds are starting to gather for the property boom and we expect a further slowing in price gains ahead of falls from later next year"

"Rising interest rates are expected to be "a big dampener". The collapse in fixed rates to 2 per cent or less played a big role in the recent boom in prices"

"Fixed mortgages have accounted for 40 per cent or so of new loans recently so are far more significant than they used to be.

But fixed rates have already started to increase and if the RBA drops its 0.1 per cent yield target for the April 2024 Government bond, further increases in two- and three-year fixed mortgage rates are likely.

If there"s one sector which feels the brunt of higher rates – it"s property.

And the reason is most real-estate is leveraged.

People borrow "$500,000" to buy homes… as it"s not the sort of money most people have under their pillow.

With rates set to rise, AMP Capital has revised its 2022 capital city average dwelling price forecast down to 5 per cent from 7 per cent and is expecting a 5 to 10 per cent decline in average prices in 2023

Sounds feasible…

But let"s dig a little deeper… as the RBA"s "yield curve control" has back-fired in ways they didn"t anticipate.

Things don"t always go according to the script…

RBA: Uber-Doves to Hawks

I want to highlight one of Oliver"s remarks:

"… if the RBA drops its 0.1 per cent yield target for the April 2024 Government bond, further increases in two-and three-year fixed mortgage rates are likely"

This is exactly what has happened….

As context, during the depths of the pandemic last March, the RBA "innovated" by mirroring Japan"s strategy of targeting a specific bond yield, but over a shorter horizon.

Their bet was this would snap bond yields (and rates) lower… but would also require less treasury asset purchases than a more generalized QE program (as we saw in the US and Europe)

And for around 12+ months or so… things were working.

Some even felt the Fed should consider the strategy.

For example, lower rates gave households (and businesses) "permission" to borrow, invest (dare I say speculate) and hire workers – in turn driving the post-pandemic recovery.

But Australia"s "yield curve control" (YCC) ended Tuesday.

The RBA abruptly dropped YCC in the face of market bets that RBA Chief Philip Lowe had it wrong… and that accelerating inflation was going to force their hand sooner.

Who knew.

Source: Bloomberg

As Malcolm Scott from Bloomberg points… there"s just one problem with the RBA"s experiment.

YCC has a particular weakness:

When the outlook rapidly changes, the central bank is stuck with a rigid policy that no longer fits the economy"s needs.

And when markets lose faith, the central bank must either buy up big to defend its target, or walk away.

What did Lowe do?

He chose to walk.

Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe said the central bank decided to discontinue its yield target on Tuesday because its effectiveness had declined as the economy improved and interest rate expectations changed.

"Given our forecasts, it is still entirely plausible that the first increase in the cash rate will not be before the maturity of the current target bond – that is, the bond with a maturity date of April 2024," Lowe said in an opening statement at an online briefing after the RBA"s policy meeting.

"But it is now also plausible that a lift in the cash rate could be appropriate in 2023. Lowe said the latest data and forecasts did not warrant a rate rise in 2022.

Earlier, the RBA left its cash rate at a record low of 0.1%, but dropped both a commitment to keeping bond yields low and its projection of no hike in interest rates until 2024.

Lowe has gone from being an "ultra dove" to a "hawk" in the space of one month.

This wasn"t priced in.

For example, last month he reiterated he wouldn"t raise the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2% to 3%… which was likely to be around 2024 (in his view)

Not now.

Rates are likely to rise much much sooner.

Again, you only have to look at the Aussie 2-year bond.

Don"t expect Australia to be alone here… others will follow.

For example, the Fed is set to outline its near-term plans tomorrow on rate hikes – but I would argue the bond market has already decided. The Bank of England meets Thursday and I expect we will see something similar.

Here"s Bloomberg:

"For other central banks that watched the RBA experiment with interest, the takeaway is not encouraging," Krishna Guha, head of central bank strategy at Evercore ISI in Washington, wrote in a note to clients before the meeting.

"Skeptics will see in the RBA experience proof that a yield target is like an FX peg and will always be vulnerable to breaking when the expected rate path shifts in a way that is not consistent with the stated target."

Putting it All Together

The Fed meeting this week will be closely watched.

Will we see a policy mistake?

That"s my view; i.e. monetary tightening into a slowing economy.

My feeling is the Fed will not want to knock equities off balance. However, as bond yields show, their hand is being forced.

Australia is a lesson learned.

Their YCC experiment failed… forcing their central bank to do a shock-about-face.

Rates will rise and property prices are likely to fall.

Artificially suppressing rates at "zero" for an extended period was caused reckless speculation (in a non-productive asset class)

Again, you exaggerate the boom and bust cycle.

It"s what central banks do with interventionist policies.

And whilst speculators have one eye on rates… the other is China.

Subject for another day…